- Home •

- Books by Category •

- Imprints •

- News •

- Videos •

- Media Center •

- Reading Group Center

Martin Walker's France: A Trip Through The Dark Vineyard

Martin Walker sets his twisted mysteries in lovely places, namely the gorgeous, historic and delicious Périgord region of France. The Périgord is widely considered the gastronomic epicenter of Europe, as well as the closest thing to heaven that devout foodies can get a taste of on earth. Our hero, police municipale Benoît Courrèges—affectionately known by townspeople as Bruno—spends the bulk of his shifts warding off the European Union bureaucrats who threaten the sanctity of local farms and market places—places that supply the pastries, baguettes, and pates he consumes from cafes and his picnic basket. The quiet town of Saint-Denis seems like an improbable setting for multiple murders, and Walker describes it with as much loving reverence as Agatha Christie would to any of the manors in which her murders were set:

The town emerged from the lush green of the trees and meadows like a tumbled heap of treasure; the golden stone of the buildings, the ruby red tiles of the rooftops and the silver curve of the river running through it. The houses clustered down the slope and around the main square of the Hôtel de Ville where the council chamber, its mairie, and the office of the town’s policeman perched about the thick stone columns and framed the covered market. The grime of three centuries only lately scrubbed away, its honey-colored stone glowed richly in the morning sun.

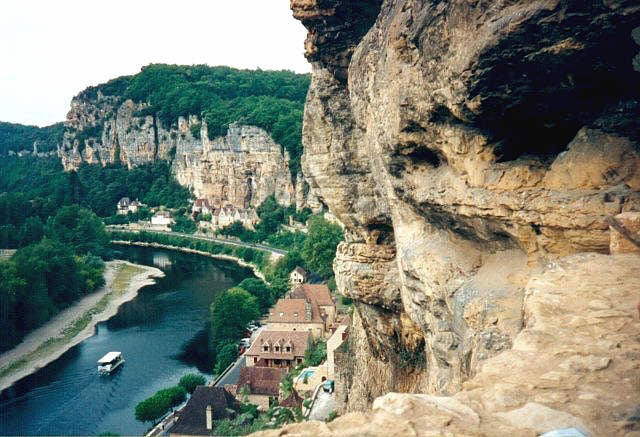

Saint-Denis is an invention of Walker’s imagination, but he directly draws inspiration for the town from the region in which he lives, borrowing details from smaller towns like Saint-Cyprien, Belvès, Les Eyzies, Siorac, Eymet, and Sainte-Alvère. Walker’s Saint-Denis is located on the River Vézère, somewhere in the quadrilateral formed by the city of Périgeux, and the capital of the Department of the Dordogne. The Hôtel de la Gare, tennis clubs, main squares, and biweekly markets featured in Walker’s novels are the charming staples of many actual French countryside towns.

In Walker’s first mystery, Bruno, Chief of Police, we’re welcomed into the town of Saint-Denis; just when it seems that the town’s worst enemy is the European Union, we learn that an elderly North African war hero who fought in the French army has been brutally murdered while eating a lunch of half a baguette, cheese, and sausage at his home. When a swastika is found carved into the corpse’s chest, Bruno and his team are left searching for clues that ultimately lead them to discover dark secrets that began under the German occupation in World War II. Even in the midst of Bruno’s sleuthing, Saint-Denis’ delights still charm him, and even a stroll through the marketplace in search of information leads us to the savory characters of everyday France, like Bruno’s favorite fruit seller, Fat Jeane, who “squealing in pleasure to see him, turned with surprising speed and proffered her cheeks to be kissed in ritual greeting.” The landscape is a vivacious character in itself; the gorgeous valley of the Vézère, brimming with natural beauty and historical sentiment, never ceases to catch Bruno’s eye. Even when he’s spelunking through one of the local caves (famous for their 12,000+-year-old cave paintings), Bruno immediately ties the lore of the region to its current-day residents:

Across the small stream that flowed into the main river, the caves in the limestone cliffs drew his eye. Dark but strangely inviting, the caves with their ancient engravings and paintings drew scholars and tourists to this valley. The tourist office called it the Cradle of Mankind. It was, they said, the part of Europe that could claim the longest part of continuous human inhabitation. For forty thousand years, through ice ages and warming periods, floods and wars and famine, people had lived there. Bruno, who reminded himself that there were still many caves and paintings that he really ought to visit, felt deep in his heart that he understood why those people had chosen to remain in this gentle valley.

In The Dark Vineyard, the latest installment in Bruno’s adventures, one of the great delicacies and valued exports of Saint-Denis—its wine—is threatened when a research station for genetically modified crops is burned down. Bruno suspects that the crime was committed by a group of local ecolos, but the fire is one of many incidents to disrupt the vineyards as winemakers compete for tracts of the region’s cherished soil. To Bruno, disrupting wine production is more than just a criminal offense—it’s blasphemy. The mere site of a broken wine bottle is enough to break Bruno’s heart. When he visits Hubert de Montignac’s esteemed wine shop, we get a glimpse of how precious the beverage can be:

For Bruno, who understood that a great part of the law’s duty was to uphold the grand traditions of France and of Saint-Denis, the cave was close to being a shrine. [. . .] All comers were invited to buy their Bergerac white, red, and rose, their vin de table and their sweet white wines for one euro a liter or less, so long as they brought their own plastic containers or bottles and did their own filling. This was where Bruno bought his everyday wine. The air smelled of wine, old and new, freshly spilled and freshly opened, at least some of it breathtakingly costly. Knowing the way to the shelf of Petrus, Bruno led his small entourage to the altar of his temple to wine, and stopped, looking down mournfully at the smashed bottle of the tiled floor. Out of respect, he removed his hat [. . .]

In this particular case, the price to pay for a broken bottle of wine is a whopping 2,200 euros. That said, there’s plenty of use crying over spilled wine. The French attitude towards wine can be incredibly frank, and yet it also seems to represent their undying passion for all-things-delicious.

In the few moments when Bruno isn’t solving murder mysteries or “protecting his neighbors and friends from the nuisances of Brussels, where the idea of food was known to stop at moules and pommes frites, and where perfectly good potatoes were adulterated with an industrial mayonnaise they did not have the patience to make themselves,” he is likely to be found eating. But unlike the stereotypical American policeman who snacks on coffee and donuts (and unlike Henning Mankell’s Wallander, who gorges on junk food and booze), Bruno opts for crusty baguettes, homemade cheeses, and magrets de canard. Walker never misses an opportunity to highlight how the history, food, and romance of the Pèrigord region are all inextricably linked. In Bruno, Chief of Police, Bruno enchants Isabelle, his co-worker-turned-love interest, with a mouthwatering picnic beside an ancient cave overlooking the Dordogne river.

Bruno boasts his culinary skills once again when Isabelle surprises him with his favorite ingredients: fresh beefsteaks, pâté, baguettes, and cheese. If you didn’t know how to marinate and grill a piece of meat beforehand, just follow Bruno’s delicious recipe:

He unwrapped the beefsteaks she had brought and made a swift marinade of red wine, mustard, garlic and salt and pepper. [. . .] He put the grill close to the coals, arranged the steaks, and then under his breath sang “La Marseillaise,” which he knew from long practice took him exactly forty-five seconds. He turned the steaks, dribbled some of the marinade on top of the charred side, and sang it again. Then he turned the steaks for ten seconds, pouring on more of the marinade, and then another ten seconds.

When Bruno isn’t working his magic with fresh, local ingredients, he’s probably dining at Fauquet’s café, which is tucked into an alley besides the Mairie (City Hall). Fauquet’s attracts nearly everyone in the neighborhood, but is a prime hang out for the citizens of Saint-Denis: old women, young children, all conversing on the cobblestone sidewalks and munching on pastries.

From the secretaries and social workers to the street sweepers and tax assessors, the staff of the Mairie would also be at Fauquet’s, nibbling their croissants and taking their coffee at the long zinc bar, eying the tartes aux citron and the millefeuilles they might take home for lunch along with the essential baguette of fresh bread and scanning the headlines of that morning’s Sud Ouest. [. . .] He enjoyed the continuity these morning movements represented. They were rituals to be respected—rituals such as the devotion of which each family bought its daily bread only at a particular one of the town’s four bakeries, except on those weeks of holidays when they were forced to patronize another, each time lamenting the change of taste and texture. These little ways of Saint-Denis were as familiar to Bruno as his own morning routine on rising in his old shepherd’s cottage in the hills above the town [. . .]

Walker’s mysteries are much more than simple who-done-its; instead, they’re a glimpse into a region of beauty and pleasure, and give readers a taste of juicy intrigue and delicious writing. Whether you’re an avid mystery reader, a Francophile, or a true gourmand, Martin Walker’s rendition of the French countryside is bound to make you want buy a one-way ticket to France.

Buy the book: Amazon | Barnes & Noble | Borders | IndieBound | Powell’s | Random House