Reading Group Center

- Home •

-

Books by Category •

- Imprints •

- Authors •

- News •

- Videos •

- Media Center •

- Reading Group Center

Newsletter

Sign up for the Reading Group Center Newsletter

Reading Group Resources

Reading Group Guides

Reading Group Tips

News & Features

Connect with Us

One Book, One Community

Community-based reading initiatives are a growing trend across the country, and we're pleased to support these programs with a wide range of resources.

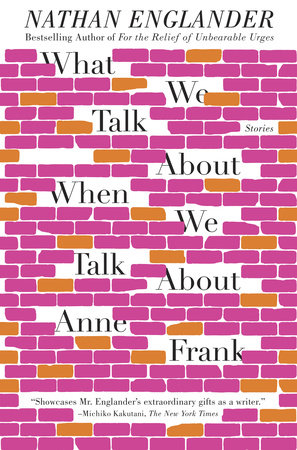

Nathan Englander Discusses Short Stories and His Writing Process

In What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank Nathan Englander returns with eight powerful stories, dazzling in their display of language and imagination, show a celebrated short-story writer and novelist grappling with the great questions of modern life. In this Q&A, we find out what draws Nathan to the short story form, and he reveals what goes on in his writing process.

Q: Your debut short story collection, For the Relief of Unbearable Urges, was a national bestseller in hardcover and paperback, winner of the PEN/Malamud award, and drew comparisons to Chekhov and Malamud. In 2009 you published a novel, but with What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank you’re back to the short story form. How does it feel?

A: How does it feel to be back to stories? It feels fantastic, is how it feels. I love this form. And I say that, not just because we’re talking about a collection, and not only because stories need extra championing for the incomprehensible-to-me fact that there’s a much smaller segment of fiction-reading folk that are willing to give a collection of stories a chance. I say it because, as both reader and writer, I have always had a deep-deep connection to the short story. I could go on pretty endlessly talking about spring-loaded forms, and what it takes to build a complete world in that space, how a story can leave you with that transformative wind-knocked-out-of-you moment if everything is just right (and I say ‘just right’ as the faux-epiphany is a gravely dangerous short-story fallback, and there’s a very thin membrane that separates the two experiences, which is, again, another reason why I love writing them. It’s surgical and delicate and so easy to go wrong).

What I’d like to make clear, simply, is that when I fell in love with books, I fell in love with the short story. There are so many great stories that have changed who I am, and how I see the world—that have, at this point, woven themselves into my very being. I don’t know how to explain it better than to say, go read Babel’s “The Story of My Dovecot” which I reference in the book, or Grace Paley’s “Goodbye and Good Luck”, or Cheever’s “Goodbye, My Brother”, or Gogol’s “The Overcoat” or “The Nose” and you will be changed forever—and then you will know what I mean.

Q: What is your writing process like? How long did it take you to write each of these stories? How many drafts do you go through?

A: Well, I’m glad you asked me this question and not my friends and my family. As I’d say, my writing process is one of great calm, during which I’m always happy-go-lucky and in good spirits. What I’ve learned over the years is that the specifics of the process are ever changing, and the cycles of the process are always the same. It’s almost a reflex to call myself a compulsive re-drafter. With both the novel, and the first collection, I’d rewrite parts endlessly, over a period of years. I had a completely different experience with this book. I held the stories in my head, sometimes for a great long time, waiting, in a way, until the stories were already written. And then I copied them down.

As for the cycle part—and this is, really, maybe where you should get my friends on the phone—after I finish writing a piece, I inevitably erase from memory what happened when writing it. I just think, Well that was fun. Or, isn’t it nice to have this finished story? And I forget, say, that every time I start, I feel forlorn, or panicked, or like the world is coming to an end. I forget that there’s always a day that feels painfully lost, or a week where the written page doesn’t yet tune to the emotional frequency in my head. But none of that time is wasted, not a second of it. That is, in fact, how the work gets done. It is a writing process. Which means, by definition, one can’t start at the end. But once I’m in the late stages, the early ones, every time, are totally forgotten. And that’s why experience helps, time passing by. As here I am telling you about that part of the process that I inevitably forget, because I’m already trying to comfort myself for the moment when I’m digging into the next book with great urgency and suddenly feel like the sky is crashing down. I will feel that way—I absolutely will. It’s just part of finding voice, finding traction. And yet, as I write it, I don’t believe it still.

Click to read the rest of our Q&A with Nathan Englander.