Reading Group Center

- Home •

- Books by Category •

- Imprints •

- News •

- Videos •

- Media Center •

- Reading Group Center

Explore Okinawa with a Literary Map for Above the East China Sea

Sarah Bird’s novel Above the East China Sea tells the interconnected stories of two girls across seventy years of Okinawan history: Tamiko, who during the 1945 Battle of Okinawa is plucked from her high school and trained to work in the Imperial Army’s horrific cave hospitals; and Luz, a teenage military brat who, years later, has moved to the island’s US Air Force base. It’s a book that, in the words of The Washington Times’s Claire Hopley, “could not have been written without deep knowledge about the history, geography and traditions of Okinawa.” To showcase Bird’s brilliant ability to conjure setting we’ve paired descriptions of key locations with one of the maps featured in the book. We hope this helps guide you in your own exploration of Bird’s richly rendered world!

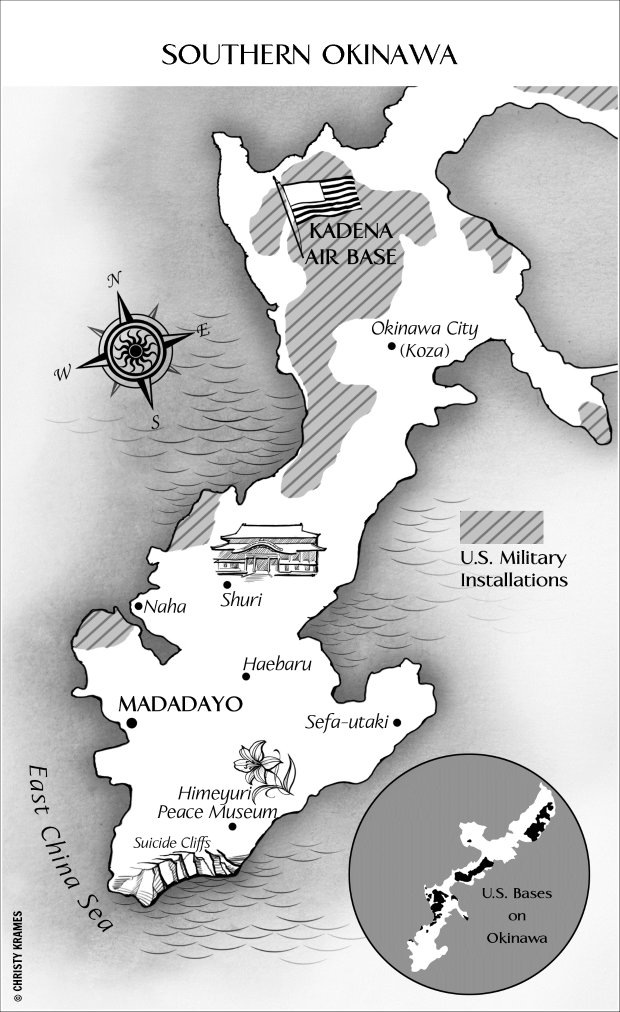

Naha

The capital and the largest city in Okinawa, Naha used to be the commercial center of the ancient Ryukyu Kingdom, which ruled Okinawa between the 15th and 19th centuries.

“In Naha, we were always awed by the majestic port where ships from Japan, Taiwan, China, and the South Sea Islands came and went. Waves lapped against the concrete piers and seagulls cried overhead. There the dockworkers, all brown as bark and naked except for their loincloths, would load and unload huge crates. Rickshaw drivers dressed in starched black jackets scrambled to be the first to pick up disembarking passengers, usually government officials sent from the mainland. As I watched, another childhood song would run through my mind. This one captured the excitement from centuries gone by, when the great tribute ships came and went from China. It reminded us of the hundreds of years when Okinawa was a trading center with silks, dyes, spices, perfumes, wine, folding screens, feathers, exotic birds and animals, swords, gold, books, medicinal herbs, even eunuchs, passing to and from Java, Thailand, Korea, Japan, and, of course, the country we were aligned with for centuries, China.”

Madadayo

The Okinawan village that the character of Tamiko is from. Luz travels to Madadayo in order to learn more about Tamiko.

“The landscape gets more jungly and overgrown the farther I walk down the narrow road. Soon the entire road is shaded by a thick canopy of trees that cools the air beneath. The noise from the highway grows more and more muffled until I can’t hear anything but birds and the breeze rustling leaves above my head. No cars pass. I notice horse turds along the road and wonder whether people in Madadayo still use carts. It’s such a peaceful place.”

Shuri

The location of the Himeyuri High School that Tamiko and her sister, Hatsuko, attend. It’s also home to Shuri Castle, the seat of the Ryukyu kings. Much of the palace was destroyed in World War II, and the tragedy of it breaks Tamiko’s heart.

“[A] sense of ease suffused me when I reached the forty-foot-high wall that encircled the royal palace and its grounds. The wall had stood for five centuries…. I knew then that what we Okinawans always said was true: “As long as Shuri holds, our kingdom will hold.” I passed beneath the grand gate inscribed with the Chinese characters meaning “Land of Peace” and entered the safety of the enchanted world within.

The castle painted in gold and vermilion could have been plucked from a fairy tale. It was just as I remembered it from my childhood visits with Mother. The tips of the castle’s vast tiled roof swept up at the edges like the horns of a water buffalo. Carved stone dragon heads spouted cool water from underground springs. Gardens and shaded forest walks sprawled out beyond the vast courtyard, suffusing the air with the tender scent of lilies.”

Haebaru

Here is the Haebaru Town Museum, which features wartime artifacts and a reproduction of the dugout bunkers that were used as military hospitals during the Battle of Okinawa. In the novel, Tamiko and her sister are among the students who are mobilized as field nurses in the final moments of World War II.

“At our quickened pace, we soon rejoined the rest of the girls from Himeyuri. The moon had risen and reached its zenith by the time we arrived at Haebaru. We craned our necks, searching for the emperor’s magnificent hospital, where we would read to wounded soldiers and bring them glasses of water, safe beneath the shield of the Red Cross.

But no red crosses greeted us. Instead, Head Nurse Tanaka led our group to a series of grassy hills with cave openings hastily concealed behind some withered foliage that looked like animals’ dens and told us that this was our destination.”

Himeyuri Peace Museum

The museum conveys the horrors of war and pays tribute to the girls who, like Tamiko, tended Japanese soldiers during the Battle of Okinawa. In the novel, Luz visits the museum in her quest to learn more about Tamiko’s story.

“Inside the Himeyuri Peace Museum, maps line the walls of the first room. Arrows swirl across the maps, indicating troop movements and reducing war to two dimensions. Farther on, cases contain artifacts from the lost paradise that the Himeyuri girls grew up in: a simple back loom for weaving banana-fiber cloth, a windup gramophone with a horn-shaped speaker, a lacquerware tea set, a tin of lilac-scented bath powder, books, pens, and, at the very end, a brooch like the one in my pocket that identified these girls as the best of the island’s best, the Princess Lily girls.”

Suicide Cliffs

These cliffs take their name from the tragedy of the Battle of Okinawa. Many Japanese soldiers and nurses jumped off the top of the protruding cliffs into the East China Sea rather than get captured by the US Army.

“The retreating Japanese army drove us farther and farther south, until at last we refugees came to the sea. We huddled by the thousands on the beach in the shade of the high cliffs. There we waited, trapped by the ocean in front of us and impenetrable thickets of Devil’s Claw bushes with thorns cruel as barbed wire on either side. Japanese soldiers perched like black crows on the cliffs above us yelled down threats that they would kill anyone who might shame them by surrendering.”

Sefa-utaki

Sefa-utaki literally means “purified place of Utaki.” It used to serve as a sacred place of worship for the native religion of the Ryukyu people. Later, when Okinawa became part of Japan, it served as a Shinto Shrine.

“At the entrance to the island’s most sacred grove, she climbed the steep, slippery steps upward into the dripping green velvet that cloaked the mystery within. Her head bowed and senses alive with the palpable presence of the kami humming in the silence about her, Mitsue had entered that hushed and hallowed spot where the noro priestesses, once the island’s undisputed spiritual leaders, had received their powers. Where for centuries the only men allowed to enter were the ancient kings of the Ryukyuan islands, who left hundreds of horses and thousands of servants waiting when they ascended these very steps to beg the kami to bless their reigns.”