Reading Group Center

- Home •

-

Books by Category •

- Imprints •

- Authors •

- News •

- Videos •

- Media Center •

- Reading Group Center

Newsletter

Sign up for the Reading Group Center Newsletter

Reading Group Resources

Reading Group Guides

Reading Group Tips

News & Features

Connect with Us

One Book, One Community

Community-based reading initiatives are a growing trend across the country, and we're pleased to support these programs with a wide range of resources.

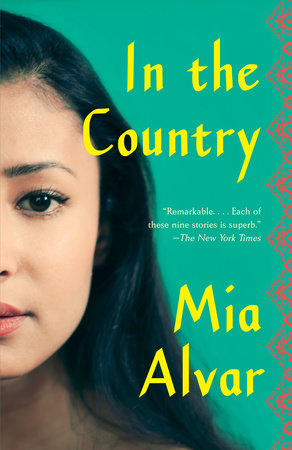

Mia Alvar Gets Into Character: An Exclusive Author Q&A

Mia Alvar has blown readers away with her debut collection of short stories, In the Country, which made it onto several “Best of 2015” lists from publications like the San Francisco Chronicle and The New Yorker. The Filipina author drew upon her own background as an immigrant and expat to compose nine stories spotlighting various experiences common within the Filipino diaspora. Filled with love, loss, and a pervasive sense of displacement, this collection is sure to provoke a great deal of stimulating discussion in your book club. In this exclusive Q&A, we ask Alvar to discuss her inspiration for the stories, as well as how she gets into so many different characters’ heads.

Reading Group Center: How much did you draw on your own life to compose these stories?

Mia Alvar: It’s hard to measure exactly how much, but each story contains some element of personal experience. As soon as I sit down to write, memories or family anecdotes get mashed up with imaginary details, my own research, and inspiration from other writers and the stories they’ve told. “The Kontrabida” came out of a trip I took to the Philippines to visit my dying grandmother. I’d been away for ten years and found it very surreal to return to my childhood home, as its yard had been converted into a sari-sari store like the one in the story. But Steve’s relationship with his parents, and the story around the Succorol patches, are fictional. Like a lot of writers, I like to distort, exaggerate, and rearrange the real world, and I enjoy the opposite process too: finding the emotional core of even the most outlandish invented scenario, and in that way help it ring true for myself and hopefully for readers.

RGC: You assume many different voices throughout In the Country—from a young man with a contentious relationship with his ailing father, to a young model struggling to find purpose, to a boy living with a disability. Where do you find your inspiration for these characters? How do you get into the right frame of mind to write about the innermost thoughts of characters with such a diverse array of personalities and backgrounds?

MA: Finding inspiration is the easy part. Sometimes I’ll want to look underneath certain archetypes or stereotypes within the Filipino diaspora, like the Middle East laborers in “A Contract Overseas” or the cleaning woman providing for her family back home in “Esmeralda.” Sometimes I borrow from history, the news, or popular culture, as with “Old Girl,” which is inspired by a prominent political family in the Philippines; and with Alice in “Legends of the White Lady,” who was originally based on the actress Claire Danes and a filming experience she had in Manila.

Fully realizing these characters on the page is the much harder part. I do a lot of research, which includes reading and thinking and note-taking and sometimes doing things and going places I think my characters would (I know exactly which church in lower Manhattan Esmeralda hides in during her first day alone in New York, even though the scene didn’t make it into the story). Ultimately, most of these details don’t see the light of day outside my notebook, but knowing what my characters eat and buy and carry in their pockets helps me to shape their voices or get a sense of their inner lives, the actions and paths they’ll take.

RGC: You play with perspective in your stories; there are examples of first-, second-, and third-person narratives in your book. How do you decide how a story should be told?

MA: Since I like to inhabit a character’s mind and body as much as possible, my drafts start out in the first-person singular more often than not. But that perspective often changes as I revise and discover what my goals are for a story. As a child, I lived in a Filipino expat community in Bahrain, which is the setting for the story “Shadow Families.” Once I brought the character Baby into that world, a woman who raises eyebrows by not behaving the way she’s expected to, it made sense to look at her from the point of view of this collective “we” and learn more about that group in the process. I wrote “Esmeralda” in the second person to invite—even force—the reader to identify with a kind of character who often becomes marginal and invisible in many people’s daily lives, and also to reflect on how difficult and awkward and imperfect it can feel to walk in someone else’s shoes. And in the title novella, “In the Country,” even though it focuses mostly on Milagros’s life, I needed the distance and knowledge of a third-person narrator to handle the political and historical scope of the story. It was fun for me to mix perspectives throughout the collection, and I hope readers like the variety, too.

RGC: The theme of displacement is very prominent throughout the book. Why did you choose to focus so much on this aspect of the Filipino cultural experience?

MA: I think that themes—or obsessions, as I tend to think of them—choose the writer, not the other way around. When I’m at my desk, scribbling or typing away, I’m usually focused on small tasks—like trying to describe a character vividly, make a scene work dramatically, or get the sound of a sentence right—rather than on themes. But of course “we write who we are,” so my own experiences of displacement as an expat and immigrant—and the generally displaced outsiderish personality that made me a writer to begin with—always surfaces, even when I’m writing about a male pharmacist or politician’s wife who’s otherwise very different from me.

RGC: Imagine you’re part of a book club discussing In the Country. What is a topic or question you’d like to pose to the group?

MA: Illness and disability come up quite often in the book, so maybe I’d ask the club why they think that’s so. What’s the connection, if any, between the more obvious themes of displacement and migration and this other obsession with disease? I wish I knew!