Reading Group Center

- Home •

- Books by Category •

- Imprints •

- News •

- Videos •

- Media Center •

- Reading Group Center

The Hidden History of the Tango

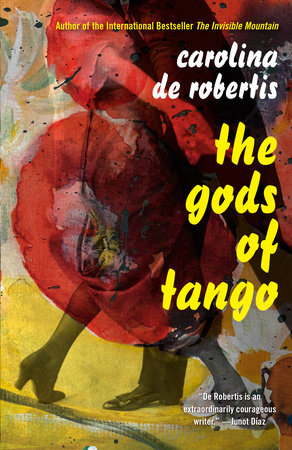

It’s always a special gift when a book simultaneously entertains and educates like Carolina De Robertis’s latest, The Gods of Tango. The novel follows seventeen-year-old Leda as she travels across an ocean to Buenos Aires and is seduced by the tango, the dance that will underscore every aspect of life in her new city. Powerfully sensual, The Gods of Tango is the erotically charged story of the quest for an authentic life against the odds in which De Robertis illuminates the often overlooked beginnings of the tango. To learn more from the author about the rich history that inspires this work, read on!

The tango has always surrounded me, part of my culture as an immigrant kid with Uruguayan and Argentinean roots, a soundtrack to my parents’ nostalgia and memories of home. I grew up accustomed to people knowing little or nothing about my countries of origin, and although the tango is in many ways highly visible in the United States—as a popular dance and as a romantic interlude in Hollywood movies—its true history and richness are rarely portrayed. I wrote The Gods of Tango in part to fill in some of those gaps, to bring to life, through fiction, the incredible hidden story of tango.

The book is set largely in the 1910s in the tenements called conventillos, which were full of immigrants who’d come to Buenos Aires from many countries—Spain, Italy, Russia, Poland, Lebanon, Germany, France—in hopes of a new and better life. In these cramped quarters, the working poor shared meals, common space, and their musical traditions as a form of internal survival; it’s from that beautiful nexus that the tango was truly born.

The tango also owes a tremendous debt to people of African descent. Few people know that at the turn of the twentieth century, Buenos Aires was one-third black. The earliest tangos, in the 1880s, included polyrhythmic drums, and Afro-Argentines, descended from enslaved people, continued to make tremendous contributions to the innovations of tango music—contributions that are all too often denied or downplayed by tango scholars even to this day.

I researched this book for four years, scouring texts from three continents, diving through archives, exploring Buenos Aires with my relatives there, living in Uruguay for over a year, taking dance lessons, and studying the violin to better understand my main character. And yet it took me a year and a half of research to discover what I consider to be one of the most incredible phenomena in tango history, almost completely ignored by scholars: female tango singers who, in the 1920s, cross-dressed in male drag in order to take the stage. Tired of being told that they couldn’t sing tangos because the lyrics were all from male points of view, that there was nothing for them to sing, they donned suits and fedoras and sang their way right into the heart of things, with their own voices, on their own terms.

When I discovered these gender-bending pioneers, Azucena Maizani among them, I was amazed. I’d already created a protagonist who cross-dresses as a man to join the male-dominated underworld of tango as a violinist. This discovery corroborated my project, and also challenged me to take it even further. Now that The Gods of Tango is a finished book, I have to say, I continue to be amazed—by this dazzling art form by the incredibly inspiring innovators who gave birth to it, from the famous to the nameless. I have strived to do them justice as best I can.

—Carolina De Robertis

Watch a performance by Azucena Maizani: