- Home •

- Books by Category •

- Imprints •

- News •

- Videos •

- Media Center •

- Reading Group Center

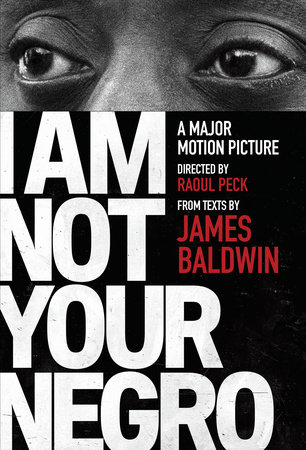

On a Personal Note: The Introduction to James Baldwin’s I Am Not Your Negro by Raoul Peck

I started reading James Baldwin when I was a fifteen-year-old boy in search of rational explanations for the contradictions I was confronting in my already nomadic life, which would take me from Haiti to Congo to France to Germany and to the United States of America. Together with Aimé Césaire, Jacques Stephen Alexis, Richard Wright, Gabriel García Márquez, and Alejo Carpentier, James Baldwin was one of the few authors I could call “my own.” Authors who were speaking of a world I knew, in which I was not just a footnote or a third-rate character. They were telling stories describing history and defining structures and human relationships that matched what I was seeing around me.

I came from a country that had a strong idea of itself, that had fought and beaten the most powerful army of the world (Napoléon’s), and that had, in a unique historical manner, stopped slavery in its tracks, achieving in 1804 the first successful slave revolution in the history of the world.

I am talking about Haiti, the first free country in the Americas (it is not, as commonly believed, the United States of America). Haitians always knew that the dominant story was not the true story.

The successful Haitian Revolution was ignored by history because it imposed a totally different narrative, which rendered the dominant slave narrative of the day untenable.

Deprived of their civilizing justification, the colonial conquests of the late nineteenth century would have been ideologically impossible. And this justification would not have been viable if the world knew that these “savage” Africans had annihilated their powerful armies (especially those of the French and the Spanish) less than a century before.

What the four superpowers of the time did, in an unusually peaceful consensus, was shut down Haiti, the very first black republic, put it under strict economic and diplomatic embargo, and strangle it into poverty and irrelevance.

And then they rewrote the whole story.

Flash forward. I remember my years in New York as a child. A more “civilized” time, I thought. It was the 1960s. In the kitchen of a huge middle-class apartment in a former Jewish neighborhood near Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn, where we lived with other members of my extended family, a kind of large Oriental rug with images of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr., hung on the wall: the two martyrs, both legends of the time.

Except the revered tapestry was not telling the whole truth. It bluntly ignored the hierarchy between the two figures, the imbalance of power that existed between them. And it thereby nullified any possibility of understanding these two parallel stories that crossed paths for a short time and left in their wake a foggy miasma of misunderstanding.

I grew up inhabiting a myth in which I was both enforcer and actor: the myth of a single and unique America. The script was well written, the soundtrack allowed no ambiguity, the actors of this utopia, whether black or white, were convincing. The production values of this blockbuster were phenomenal. With rare episodic setbacks, the myth was life, was reality. I remember the Kennedys, Bobby and John, and Elvis, Ed Sullivan, Jackie Gleason, Dr. Richard Kimble, and Mary Tyler Moore very well. On the other hand, Otis Redding, Paul Robeson, and Willie Mays are only vague associations, faint stories “tolerated” in my memory’s hard disk. Of course there was Soul Train on television, but it came much later and aired on Saturday mornings, when it wouldn’t offend any advertisers.

Medgar Evers died on June 12, 1963. Malcolm X died on February 21, 1965. And Martin Luther King, Jr., died on April 4, 1968. Over the course of five years, the three men were assassinated.

They were black, but it is not the color of their skin that connected them. They fought on quite different battlefields. And quite differently. But in the end, all three were deemed dangerous and therefore disposable. For they were eliminating the haze of racial confusion.

Like them, James Baldwin also saw through the system. And he knew and loved these men.

He was determined to expose the complex links and similarities among Medgar, Malcolm, and Martin. He planned to write about them. He was going to write his ultimate book, Remember This House.

I came upon these three men and their assassinations much later. Nevertheless, these three facts, these elements of history, form the starting point, the “evidence” you might say, for a deep and intimate personal reflection on my own political and cultural mythology, my own experiences of racism and intellectual violence.

This is exactly the point when I really needed James Baldwin. Baldwin knew how to deconstruct stories and put them back in their fundamental right order and context. He helped me connect the story of a liberated nation, Haiti, and the story of the modern United States of America and its own painful and bloody legacy of slavery. I could connect the dots.

Baldwin gave me a voice, gave me the words, gave me the rhetoric. At his funeral, Toni Morrison said, “You gave me a language to dwell in, a gift so perfect it seems my own invention.” All I knew or had learned through instinct or through experience, Baldwin gave a name to and a shape. I now had all the intellectual ammunition I needed.

For sure, we still have strong winds pummeling us. The present time of discord, ignorance, and confusion is punishing. I am not so naive as to think that the road ahead will be without hardship or that the challenges to our sanity will not be vicious. My commitment is to make sure that this film is not buried or sidelined. And this commitment is uncompromising. I do not wish to be, as James Baldwin put it, an “eccentric patriot” or a “raving maniac.”

|