Reading Group Center

- Home •

- Books by Category •

- Imprints •

- News •

- Videos •

- Media Center •

- Reading Group Center

Rufi Thorpe’s 4 Favorite Books About Fathers and Daughters

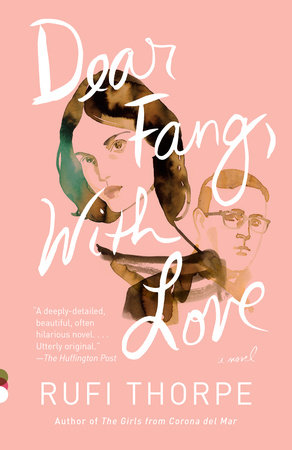

Rufi Thorpe is one of our favorites here at the Reading Group Center. Her first novel, The Girls from Corona del Mar, is a searing exploration of the changing friendship between two women over the course of their lives. Rufi shared her favorite female friendships in literature with us to celebrate the release of The Girls from Corona del Mar, so moments after finishing her latest novel, Dear Fang, With Love, we knew exactly what kind of book we wanted her to recommend next. Dear Fang, With Love is a spellbinding novel about a father and his seventeen-year-old daughter, Vera—ravishing, troubled, wildly intelligent Vera—who travel to Europe hoping that an immersion in their family’s history might help them forget his past mistakes and her uncertain future. Inspired by Vera’s relationship with her father, we asked Rufi to share her favorite literary father-daughter relationships.

I grew up not knowing my father, so it is rather odd that I have written a novel about a father and daughter. When I told my best friend I was writing a father/daughter book, she snorted wine out her nose. If there is one thing I know nothing about, it is the relationship between fathers and daughters. Which is perhaps what makes the subject so fascinating to me.

Everything I know about fathers and daughters I learned in books. These are some of the fictional fathers who formed me.

A Widow for One Year by John Irving

John Irving is one of my favorite writers, and A Widow For One Year may be my favorite of his books, in part because its protagonist, Ruth Cole, is powerful, well drawn, complicated, and delightful. The book, like much of Irving’s work, is too long and chaotic for adequate summary, but the bulk of the psychological action lies in Ruth’s relationship with her father, an alcoholic womanizer who sleeps with her best friend. It also has one of the best rape revenge scenes I’ve ever read and it involves a squash racquet.

A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley

I would read a grocery list if it was written by Jane Smiley. The psychological depth of her characters and the insight with which she describes familial relations is just astounding. A Thousand Acres is a reimagining of King Lear wherein a widower father decides to turn over his farm to his three daughters.

Smiley is at her best in articulating the ineffable intricacies of our assumptions and mental constructs:

“When I went to first grade and the other children said that their fathers were farmers, I simply didn’t believe them. I agreed in order to be polite, but in my heart I knew that those men were impostors, as farmers and as fathers, too. In my youthful estimation, Laurence Cook defined both categories. To really believe that others even existed in either category was to break the First Commandment.”

American Pastoral by Philip Roth

Jane Smiley actually once criticized this novel in an interview with The Paris Review for being an inaccurate portrayal of the way a man would ever relate to his daughter, for one of the crucial turning points is when Levov, our protagonist, kisses his own daughter, which brings about a moment of guilt that, while not repeated, becomes a defining one for the father who ultimately loses his daughter to radical political action and finally extreme religious devotion. Smiley said, “[I]t wasn’t believable and it showed me that he didn’t know … about having daughters.”

I really liked that she said that because I have a hard time questioning Roth. I find him so seductive: the long sentences coil around me, and the logic and the rhythm become hard to separate until I am lightheaded and breathless and not sure what is going on. Nonetheless, this is one of my favorite novels, perhaps because I too don’t know shit about having daughters. I will forgive Roth his chimerical moments in exchange for his obsessively ruminative mind:

“What was astonishing to him was how people seemed to run out of their own being, run out of whatever the stuff was that made them who they were and, drained of themselves, turn into the sort of people they would once have felt sorry for. It was as though while their lives were rich and full they were secretly sick of themselves and couldn’t wait to dispose of their sanity and their health and all sense of proportion so as to get down to that other self, the true self, who was a wholly deluded fuckup.”

The Children’s Crusade by Ann Packer

If, for a moment, you want a break from fathers kissing their daughters, molesting their daughters, or sleeping with their daughters’ best friends (these being the three main activities of fathers as far as Literature is concerned, which is why I was always secretly a little glad I didn’t have one), The Children’s Crusade is a reprieve. It features a good father, a really good one, an Atticus Finch–style dad of the old school.

The Children’s Crusade follows the four Blair children, raised by their endlessly good, kind, and moral pediatrician father and their terrible mother. The book continually hints at how terrible the mother is and how wounded the children are by her, but by book’s end the monstrous mother is revealed as nothing more than an aspiring artist, the terrible harm she inflicted on her children nothing but too much time spent in her studio, too much insistence that she had a right to a life of her own. Packer masterfully plays with our expectations, forcing us to examine our assumptions about gender, parenthood, and the myth of the selfless mother.