- Home •

- Books by Category •

- Imprints •

- News •

- Videos •

- Media Center •

- Reading Group Center

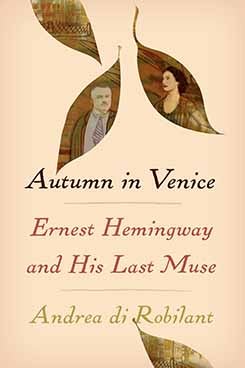

‘Autumn in Venice’ by Andrea di Robilant

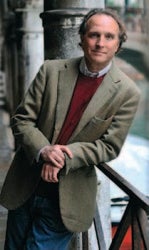

WHO: Andrea di Robilant

WHAT: AUTUMN IN VENICE:

Ernest Hemingway and His Last Muse

WHEN: Published by Knopf June 11, 2018

WHERE: Venice

WHY: “This lively and affecting double portrait

brings a fresh perspective to the much-examined life

of an all-too-human writer.

“Andrea di Robilant goes deep into an emotionally disturbing period of Papa Hemingway’s life. The result is a love story on two levels — one involving an alluring city, the other Hemingway’s regrettably immature propensity for seeking extramarital bliss.

“Hemingway fell hard for an Italian woman 30 years his junior. He was traveling with wife number four, Mary Welsh Hemingway, into the mountains for skiing and into Harry’s Bar for drinking with a motley pack of nobles and thrill seekers, including di Robilant’s great-uncle. After 18-year-old Adriana Ivancich caught Hemingway’s gaze and naively returned it, he alternated between marital disruption, extreme moodiness, and creative regeneration.

“The first half of the book amounts to a making-of-a-novel backgrounder: Across the River and into the Trees (1950) was Hemingway’s postwar portrait of a 50-year-old veteran scouring his bitter memories and courting a 19-year-old Italian countess. Hemingway deluded himself into thinking it was his best work; many critics savaged it. Di Robilant follows Hemingway through his mostly tragic last decade to his suicide in 1961, and Ivancich to her suicide in 1983.”

–Steve Paul, in a starred review for BOOKLIST

“A sensitive recounting of a writer’s doomed fantasy.” –KIRKUS REVIEWS

. . . . .

FROM THE BEGINNING OF THE BOOK:

In the autumn of 1948, Ernest Hemingway and his fourth wife, Mary Welsh, traveled to northern Italy and visited Venice for the first time.They had not planned it that way: their initial intention, when they had sailed from Cuba, was to disembark in the south of France, drive across Provence, and head on to Paris. But a mechanical failure forced the ship to dock in the port of Genoa. Hemingway had known the city well in his youth: it was from Genoa that he had sailed home on the Giuseppe Verdi after World War I, and it was to Genoa that he had returned several times in the twenties, both on assignment as a young reporter and on holiday with his first wife, Hadley Richardson.

As Hemingway set foot on Italian soil, old memories resurfaced, and a longing to see the country took over. He and Mary set o on a serendipitous journey that took them to the lake region in Lombardy, then on to the Dolomites, and finally down into the Veneto, and to Fossalta di Piave, the little town huddled on the southern bank of the Piave River, where Hemingway had stared death in the face on the night of July 8, 1918—a brash kid from Oak Park, Illinois, two weeks away from his nineteenth birthday.

Fossalta is no more than fifteen miles from Venice as the crow flies. Young Hemingway never had a chance to visit the city—he was injured only days after reaching the front line. He finally managed to see it, thirty years later, arriving with Mary on a clear, moonlit evening. Venice was all he had hoped for and more— “absolutely god-damned wonderful.”

Hemingway was less than a year shy of his fiftieth birthday. He hadn’t published a novel in nearly a decade and was struggling with a rambling manuscript. Critics considered him an author of the past; the new young writers coming out of World War II were getting all the attention. His marriage offered few pleasures. Indeed, the trip to Europe was at least in part an attempt to revive a languishing union.

On this score, the first few weeks in Italy looked promising: Hemingway was in excellent form, and Mary had rarely seen her husband in such a pleasant mood. But in early December, things took an unexpected turn. At a duck shoot in the lagoon, Hemingway met and fell in love with Adriana Ivancich, a striking eighteen-year-old just out of finishing school. Hemingway later wrote that when he saw Adriana the first time he felt as if “lightning had struck”—a hackneyed expression he probably would never have used except perhaps in the original, mythological sense, as a way to underscore his helplessness in the face of the gods’ capricious deed.

Media Resources:

Media Resources:

About the book and author | Download the jacket | Download the author photo

Knopf. With 11 illustrations. 337 pages. $26.95

ISBN 978-1-101-94665-7

To interview the author, contact:

Kathy Zuckerman | 212-572-2105 | kzuckerman@penguinrandomhouse.com