Reading Group Center

- Home •

-

Books by Category •

- Imprints •

- Authors •

- News •

- Videos •

- Media Center •

- Reading Group Center

Newsletter

Sign up for the Reading Group Center Newsletter

Reading Group Resources

Reading Group Guides

Reading Group Tips

News & Features

Connect with Us

One Book, One Community

Community-based reading initiatives are a growing trend across the country, and we're pleased to support these programs with a wide range of resources.

Learning from Our Past: A Q&A with Julie Orringer

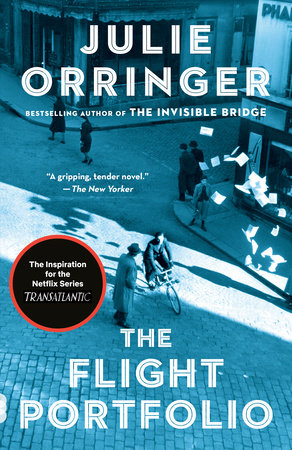

Julie Orringer’s The Flight Portfolio is a stirring historical novel based on real events. It follows Varian Fry, an unlikely hero, as he works tirelessly to save some of Europe’s greatest minds from the Nazis. Set against the backdrop of World War II France, The Flight Portfolio vividly evokes a sense of time and place, and it’s a perfect choice for reading groups.

Julie was kind enough to answer a few of our questions about this deeply researched and engrossing tale. Read on to learn more!

Reading Group Center: The Flight Portfolio is a work of fiction, but it features many real-life historical figures. How did you first learn about Varian Fry and his rescue network? Why did you decide to write a book with him at its center?

Julie Orringer: I learned about Varian Fry while researching my last novel, The Invisible Bridge. As I studied the terms of France’s 1940 armistice with Germany, I read about the Surrender on Demand Clause, which stipulated that the Nazis could deport any current or former German citizen in France for trial in Germany. I Googled the phrase surrender on demand and up came a memoir by that title written by Fry. When I read the memoir, I couldn’t believe I’d never heard about this heroic American who’d gone to France in 1940 to find and save writers and artists blacklisted by the Nazis. He had no lifesaving experience and few resources, but he managed to save more than two thousand of Europe’s most renowned artists. I thought his story begged to be told. And not just the story of his heroism, but also the one that hadn’t been recorded in the history books: the inner story of what motivated him to step beyond the confines of his New York life and perform world-changing acts.

RGC: How much research did you undertake before writing The Flight Portfolio? What did it involve?

JO: I researched Varian Fry’s life and work for about three years before I started writing the novel. First I read Fry’s memoir and whatever I could find online. Then I moved to New York for a fellowship at the New York Public Library’s Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers; the fellowship gave me a year to learn more about Fry’s clients—artists like Marc Chagall, Hannah Arendt, Max Ernst, and André Breton—and to read biographies and histories that illuminated Fry’s life. Next, I went to Harvard for a year, to the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, where Varian Fry’s student records had just been unsealed. I learned a great deal there about who Varian had been before he undertook his lifesaving work. And finally, back in New York, where I still live, I spent many hours at Columbia University’s Varian Fry Collection, held in the Manuscripts and Archives division of Butler Library. The archive contains Varian’s letters from his time in France, along with hundreds of photos he took, correspondence with the artists he saved, and records of what his colleagues observed in the concentration camps of France, among other things. I also went to Marseille to conduct research on the ground—I walked around the neighborhoods where Varian lived and worked, took the train out to the suburb where he and his Surrealist clients lived in a country villa, and explored the surrounding towns where he went on the weekends to explore and relax.

RGC: There is a devastating and provocative moral question at the heart of the story: who deserves to be saved? How did you grapple with that question during the writing process? What did you hope readers would take away from the final result?

JO: Yes, this is the novel’s unanswerable question, one that Varian himself struggled with until the end of his life. His organization, the Emergency Rescue Committee, had limited resources; how to allocate them? He knew that he’d eventually be kicked out of France for breaking its laws on behalf of his clients; how to decide which cases were most important, knowing he wouldn’t have time to address them all? At first Varian was under a mandate by his organization to save only the most prominent, but when he realized how bad things were on the ground—both in cities like Marseille and in the concentration camps—he realized that he had to expand his rescue operation to include as many refugees as possible, even if it meant angering those who ran the Committee’s offices in New York. In writing the novel, I explored Fry’s moral conundrum both in the public sphere—how to address the difference between what he knew was right and what his parent organization demanded?—and in the private sphere. I knew Fry’s choices must have been influenced by powerful personal factors, some of which history might not have recorded. Along these lines I introduced a few plausible complications—notably the arrival of a former lover who recruits Varian’s help in trying to save a friend’s son. I suppose I wanted readers to feel Varian’s humanity, to understand that love, frustration, and anger might have influenced him as much as intellect and moral reason.

RGC: What relevance do you think the story has for readers today? How does it fit into our current political and cultural moment?

JO: When Varian Fry found the political conditions of his time to be intolerable, he took a clear position. He refused to sit by and let the Nazis destroy men and women who had created works of art that changed the way we saw the world. And he refused to be daunted by the United States’ reluctance to accept Jewish immigrants. Instead, he used every resource and contact he had to save his clients’ lives. The novel also addresses racial injustice: Nazi Germany’s persecution of the Jews, and the United States’ deeply entrenched history of racism. And finally, it tells the story of what it feels like to suppress one’s own sexual identity, to be forced to live a straight life in order to conform to social conventions.

We now face a number of crossroads in our country. Will we keep our borders impermeable, or will we let in the refugees who have a desperate need for our country’s freedoms? Will we let racial injustice persist within our borders, or will we change the underlying structures that perpetuate it? And will we support people of every sexual orientation and gender variation, or will we let antiquated prejudices stand? Varian’s work proves to us that a single human being’s intelligence and persistence can make a difference for thousands of others. How can any of us be complacent in the face of that story?

RGC: Are there any characters or aspects of the book that feel particularly personal to you?

JO: During the years I was writing this book, I gave birth to my two children and raised them from babyhood to elementary-school age. When I began writing, I had no idea that a father’s love for his son would determine the course of the novel; the story seemed to me to be all about the struggles of war and the pull of one man’s love for another. But as the novel progressed—and as I moved deeper into the complications of motherhood myself—I found myself thinking more deeply about how our loyalties as parents are, in a way, set forever, and how a parent’s love might present particular moral complication in times of war. Considering how much time I spend thinking about my own children’s needs, I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that parenthood—its emotional claims, its irrationalities, its joys—became one of the most important elements of this book.

RGC: What is the best writing advice you’ve ever received? What about reading advice?

JO: The best writing advice I received was from Marilynne Robinson, at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, who told me when I was twenty-two to stop trying to write like others (in this particular case, she meant Western American white men) and to return to writing like myself. She gave me that piece of advice at a time when my own perspective, and my own identity, weren’t particularly well represented or appreciated in the writing world. But she helped me see that there was no other honest way forward, and I’ve always been grateful for that. As for reading advice, I have to cite my mother, who told me a hundred times to turn on the light or I’d ruin my eyes.

RGC: Imagine you’re part of a book club discussing The Flight Portfolio. What is a topic or question you would like to pose to the group?

JO: I’ll pose a question a writer friend asked me after she read a draft: how was it possible that Fry and his associates—most notably, the surrealist artists he lived with at the Villa Air Bel, outside Marseille—managed to throw such fabulous parties in the midst of a war? Not just managed practically speaking, when there was so little food and so little money, but also emotionally speaking, when the political circumstances were so dire? Maybe another way of asking this question is as follows: how did Fry and his clients muster the fortitude to go on living richly and defiantly in spite of everything?