Reading Group Center

- Home •

-

Books by Category •

- Imprints •

- Authors •

- News •

- Videos •

- Media Center •

- Reading Group Center

Newsletter

Sign up for the Reading Group Center Newsletter

Reading Group Resources

Reading Group Guides

Reading Group Tips

News & Features

Connect with Us

One Book, One Community

Community-based reading initiatives are a growing trend across the country, and we're pleased to support these programs with a wide range of resources.

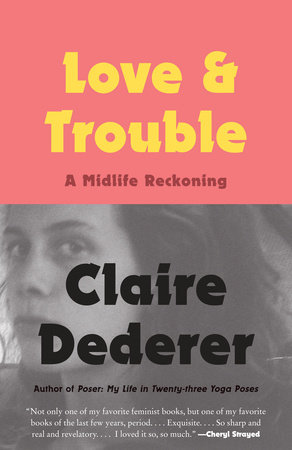

Claire Dederer’s Favorite Mothers in Literature

When Claire Dederer, happily married mother of two, turned forty-four she began to have what she can only describe as “a lot of extremely inconvenient feelings”—feelings of recklessness, of impatience, and of a kind of voluptuous erotic reawakening. In Love and Trouble, Dederer shifts between her present experience as a middle-aged mom in the grip of unruly and mysterious new hungers and her recollections of herself as a teenager—the last time she experienced life with such heightened sensitivity and longing—two periods uncannily similar in their emotional intensity. To celebrate the paperback release of this wickedly funny and piercingly honest memoir, Dederer shared some of her favorite fictional mothers with the Reading Group Center.

I’ve always been attracted to the kind of mother who lives a life larger and more complicated than what is implied by that simple noun: mother. I loved Marmee and Caroline Ingalls of course—they are the ur-moms of children’s books—but as a young reader the mother I loved best was the one from Edward Eager’s Half Magic and Magic By the Lake. These totally delightful books, written in the 1950s but set in the ’20s, center around four children and their mother, Alison, who is widowed and therefore single, harried, distracted, and above all working. The four children adore their mother, and her hard-workingness is treated as one and the same as her lovability.

The mothers I love as a grown-up reader also belong to the world as much as they belong to their children. They are unsettled mothers, mothers who don’t leave but do admit they possess a humanity that extends beyond the four walls of a house. In nineteenth-century literature, such mothers were given a gloss of tragedy; Anna Karenina is one. But the twentieth century brought a flourishing of complicated, ambivalent mothers. Perhaps the perfect example of this type is Anna Wulf from Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook, the subject of maybe the most famous passage of maternal ambivalence in all of literature:

“Janet looked up from the floor and said, ‘Come and play, mummy.’ I couldn’t move. I forced myself up out of the chair after a while and sat on the floor beside the little girl. I looked at her and thought: That’s my child, my flesh and blood. But I couldn’t feel it. She said again: ‘Play, mummy.’ I moved wooden bricks for a house, but like a machine. Making myself perform every movement. I could see myself sitting on the floor, the picture of a ‘young mother playing with her little girl.’ Like a film shot, or a photograph.”

Anna Wulf is politically radical, sexually active, emotional labile—and yet she remains a committed mother through the book (though of course Lessing’s own history as a mother was more complex—she left two children behind in Rhodesia when she moved to London, bringing along her third child, plus a manuscript of her first novel in her suitcase).

My favorite mothers from literature—whether fiction or memoir—follow in Anna’s wavering, wayward footsteps. Rachel Cusk has given us a career’s worth of ambivalent, brainy, questioning mothers who make me feel less alone, from her novel Arlington Park to her current trilogy (Outline, Transit, and Kudos)—to her underappreciated and even occasionally reviled memoir of motherhood, A Life’s Work. I think, generally speaking, if your portrait of motherhood is reviled, you’ve probably hit the right tone.

In a more comic mode, the mother in Shirley Jackson’s Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons faces her maternal battles with a rueful, mid-century wryness and a notable air of detachment.

Perhaps because of this love of mothers who transcend and subvert their role, my favorite mother in all of literature just might be transwoman Anna Madrigal (what’s with all these Annas?) from Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City series. Yes, she’s the biological parent to one child, but really she’s spiritual mother to a chosen family of misfits. When I think of the mother I’d most want to lay a cool hand on my fevered forehead and dispense some life advice, I think of Anna Madrigal. Who better to undermine our most established notions of what a mother ought to be?

—Claire Dederer