Reading Group Center

- Home •

- Books by Category •

- Imprints •

- News •

- Videos •

- Media Center •

- Reading Group Center

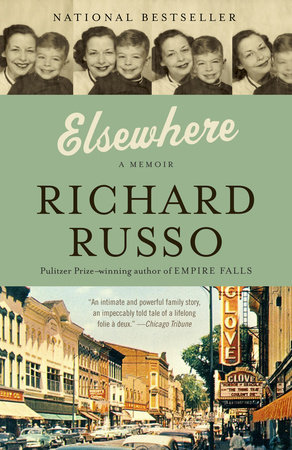

Elsewhere

By Richard Russo

1. In the Preface, Russo writes that “What follows in this memoir—I don’t know what else to call it—is a story of intersections: of place and time, or private and public, of linked destinies and flawed devotion” [p. 12]. In what ways do place and time, private and public, linked destinies and flawed devotion intersect in the book? Why does Russo hesitate to call it a memoir? In what sense is it more than a memoir?

2. As he reads the book about OCD, Russo writes: “As dispiriting as it was to recognize my mother on virtually every page...it was even more painful to recognize myself as her principal enabler. Because, like alcoholics and other addicts, obsessives can’t do it on their own” [p. 225]. Is Russo right to take some responsibility for his mother’s mental turmoil? In what ways does he enable her? Could he have responded differently?

3. How might Jean’s life have been different if she had been properly diagnosed and treated for OCD?

4. Of becoming a writer, Russo reflects that, “Somehow, without ever intending to, I’d discovered how to turn obsession and what my grandmother used to call sheer cussedness...to my advantage. How and by what mechanism? Dumb luck? Grace? I honestly have no idea. Call it whatever you want—except virtue” [p. 166]. How can Russo’s ability to harness his obsessions be explained? Why does he refuse to call it “virtue”? How is it that obsessiveness can be so destructive for one person and so fruitful for another?

5. What powerful mixture of feelings does Russo experience when his father tells him bluntly that his mother is crazy? What are the most challenging aspects her behavior? What does Russo see as the source of her anxieties and panic attacks?

6. In what ways are Rick’s challenges in dealing with an aging parent that universal? In what ways are they specific?

7. Near the end of the book, Russo writes that “novelists, if they know anything, should know how important stories are, that narratives often provide the key to things that run deeper in us, in our basic humanity, than can be diagnosed by even the most skilled physician. Given how often I’d heard it, I should have recognized the importance and meaning of my mother’s Easter story, the one where she and her sister got new dresses and my grandmother did not” [p. 241]. What is the importance and meaning of his mother’s Easter story? Why and in what ways are stories crucial for understanding—and even shaping—our lives?

8. How has the story that Russo tells in Elsewhere helped him arrive at a greater understanding of his mother and their own shared narrative? What does he know at the end that he didn’t know at the beginning?

9. Why does Russo attribute his becoming a writer to his mother’s influence? How did she inspire him to write?

10. In what ways does Elsewhere explore the difficulties that virtually everyone must face in dealing with an aging parent? What aspects of the memoir are unique to Russo’s own situation?

11. In the Acknowledgements, Russo says: “To my mother I owe, well, just about everything, and to some readers these pages may seem a strange way to repay such an enormous debt” [p. 246]. Why does Russo feel such gratitude toward his mother despite the many challenges of taking care of her? Does the book seem a strange way to repay the debt?

12. Elsewhere is not only about Russo and his mother but also about the town of Gloversville where Russo grew up. In what ways does the trajectory of Gloversville, from thriving manufacturing town to impoverished post-industrial backwater, mirror what’s happened in much of America over the past seventy years? Why do the tanneries and related glove-making businesses move their operations out of the U.S.? How does this affect Gloversville? In what ways did those companies, exploit and endanger both their workers and the health of the town itself? Are the tanneries guilty of what Russo calls “corporate murder” and “corporate rape” [p. 231]?

13. How does this nonfiction treatment of his hometown differ from the fictional versions of Gloversville Russo has written about in his novels? What does this treatment add to his fictional portraits of the house and town that, he says, would “nourish [his] creative life for more than three decades”? [p. 239]