Pugilists, Snowflakes, Baba Yaga, and More: Emma Richler on Her Influences for Be My Wolff

When two characters are as close as Rachel and Zachariah, the adoptive siblings turned star-crossed lovers in Emma Richler’s novel Be My Wolff, it is no wonder that they have their own vocabulary, references, and—it seems—their own world. Having not only the experience of a shared childhood, but also an intimacy that only soulmates can find, their conversations bounce off each other as they flit through boxing, folklore, Charles Dickens, and the natural world. We enjoyed hearing the author tell us more about her various influences, the personal connections to the works she references, and how they found their way from her life to the page. We hope your book group will too! Plus she gave us plenty of new ideas for our TBR pile, and you know how much we love that!

I spent a dozen years writing Be My Wolff, and yet the themes and characters that emerged in the years of composition were no doubt born and burgeoning for many years before I ever began to lay out this novel on the page, burgeoning and simmering at various levels of consciousness. I feel this must be true for many writers of fiction, how one is emotionally and intellectually drawn to people and subjects from the earliest days, for whatever reason of birth, inclination, sensibility, and how these concerns, sensations, and fascinations take shape only when one is compelled to give them expression, when these preoccupations suddenly find common ground, and a stage to play on. I don’t know how else to explain it. In a sense, I am at the mercy of all these voices and leanings. This is not a conceit, it’s just the business of alchemy, of the mechanics of experience and imagination.

(Photos courtesy of the author)

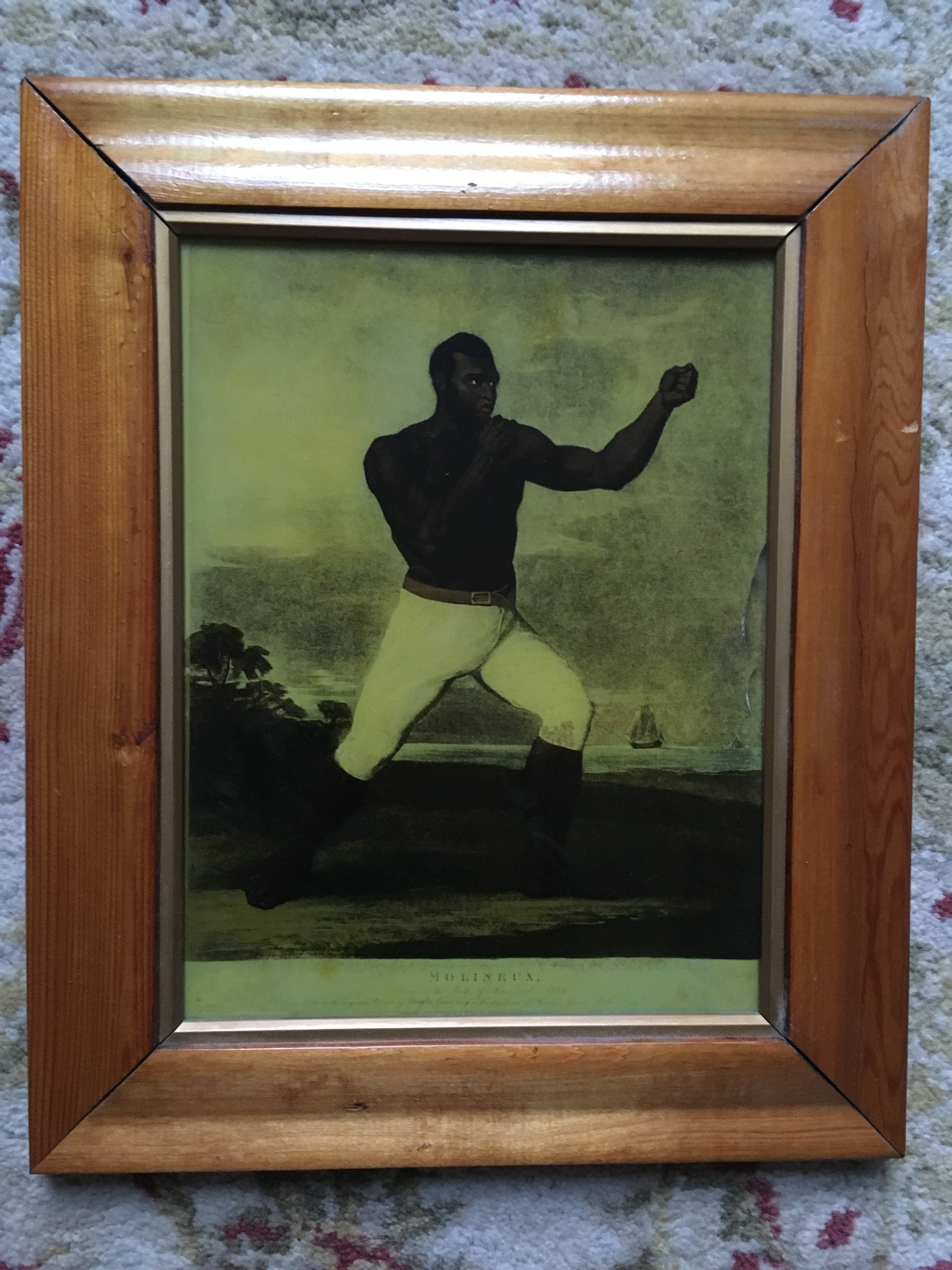

I remember a day in London when my mother brought home two framed prints of the Regency pugilists Daniel Mendoza and Tom Molineaux for my father, Mordecai, who was a boxing fan. I was nine years old and was instantly fascinated by this pair of portraits. I saw them on different walls from that date, in different houses and countries as we moved from England to Canada. My mother hung the pictures so that the fighters faced away from each other. She did not like them to appear to be fighting each other, squaring up, as both men were portrayed in attitude. I found this, as well as their place in our homes, prepossessing and somehow reassuring. Yet there is nothing reassuring about boxing, about men hitting other men in the head and body hard enough to kill and maim, but, as for many writers before me, boxing has an undying allure. There is nobility in this contest and there is horror in the conflict, which is to say, the ring is sometimes a microcosm for the human condition.

I often fingered the boxing books on my father’s shelves, especially the facsimile of Pierce Egan’s Boxiana and the book on Regency boxing by John Ford, as well as the book containing the famous essay by William Hazlitt written in 1822 about the fight between Bill Neate and Tom Hickman a year earlier, all of which titles figure in Zach and Rachel’s world in Be My Wolff. I have copies of my own now and they sit on my shelves, shelves that now groan under the weight of perhaps 150 other books on boxing from its beginnings to the present day, some of which are particularly literate and sensitive reads, namely Hugh McIlvanney’s On Boxing, Donald McRae’s Dark Trade and Mark Kram’s Ghosts of Manila to cite a few.

Ten years after my father died, my mother sold our country house overlooking Lake Memphremagog in the Eastern Townships of Quebec, where those portraits of Daniel Mendoza and Tom Molineaux hung on a wall of the snooker room she had built for my father on a side of the house with a beautiful view of the lake. She gave me those portraits, though I had never asked for them. I never asked for anything. I just wanted him back, walking around that room with his snooker cue, under the portraits my mother bought for him at an auction in London almost a lifetime ago.

Rachel Wolff creates an alter ego for Zachariah out of love and, chiefly, in an effort to understand him better and because she has a fierce belief in the laws of pattern formation, and a sense of fate and historical truth. Sam the Russian, in her story, is a friend of the very young Charles Dickens, a writer whose stories and voice have always been a treasure trove for me. And so Dickens’s first book, his collection of essays, is an influence on Rachel, on her grasp of times past and present. The language, like the language of the Regency boxing writers and fans—the Fancy—permeate Zach and Rachel’s life and world. The Pickwick Papers, in which Samuel Pickwick and company choose to adorn their waistcoats with buttons inscribed with the letters P.C. for “Pickwick Club” is a deliberate nod by Dickens to the Pugilistic Club of the times, an organization founded for the benefit and regulation of early nineteenth-century pugilists, the origin of which is described by Pierce Egan in Boxiana. Things come together in strange and felicitous ways! Here is an example of common ground, of my own childhood fascinations overlapping. And Dickens, too, of course, was drawn to the ring and the sad bruised and noble presence of prizefighters.

I read many of the works of Daniel Defoe—beginning with Robinson Crusoe in childhood, complete with its extraordinarily long subtitle, and continuing with his satirical poem The True Born Englishman and his travel writing and his A Journal of the Plague Year, written in 1722 about the plague of 1665. Robinson Crusoe, adventurer, became something of a symbolic figure for Sam the Russian in my novel, and for Charles Dickens and Zachariah Wolff.

My keen obsession with the laws of pattern formation, the theories of chaos and emergence were a little mysterious to me in the run up to the writing of Be My Wolff, yet I have learned to trust my instinct to read about certain subjects prior to starting a new book. There must be a reason, I tell myself. And there was. I read and reread Ian Stewart’s eloquent What Shape is a Snowflake? and it led me to further reading and other titles, including several others by him, so that many of the ideas and theories raised in these often complex books affected me deeply—and through me—Rachel and her father, Lev, a scientist of emergence and meteorology.

Fairy tales! What child has not been perplexed and disturbed by fairy and folk tales? And Russian tales are singularly outlandish and disturbing, it seemed to me. I remember especially the Arthur Ransome interpretation of the Russian tales, beautifully and tellingly written, devoid of sentimentality, full of muscularity and enchantment. Ransome spent years visiting Russia, studying folklore, covering the First World War on the Eastern Front and the Russian Revolution. And there he met his second wife to be, Trotsky’s secretary at the time.

My fascination for Russia and things Russian dates from childhood. In my adolescence, I read Eugene Onegin and Pushkin’s poetry. I read Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time three times. I read Gogol’s strange and wonderful Dead Souls and marvelled at the famous metaphorical image of Russia that comes at the climax of the novel, Russia as a speeding troika, going who knows where . . . I fell in love with the plays of Anton Chekhov. I painted Napoleonic toy soldiers as a teenager, spending hours and hours at weekends constructing French-made 54mm figures of delicately molded plastic and straps made from strips of parchment and gun furniture fashioned from minuscule bolts of metal. I painted them in oils, which took weeks to dry. I read about military campaigns and, in adulthood, devoured histories and biographies of the Napoleonic wars, the Retreat from Moscow, Tsarist Russia, the lives of Pushkin, Lermontov, Turgenev, Tolstoy, Platonov, Mandelstam, Akhmatova, etc. This book is full of Russia. The Wolffs are émigrés, and Rachel is first-generation English. Her sensibilities are as Russian as they are English and the influence of folk tale, the weight of history, the sense of exile and place and loss, the importance of the human voice in song, the notion of destiny—all of these motifs abound and prevail in Be My Wolff.

Rachel is a naturalist as well as an illustrator and cartographer. My own interest in nature found some kind of expression here and I was able to use my delight in the writings of the diarist and naturalist Gilbert White in his The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne. I now own a beautiful Folio Society edition with extraordinary illustrations and appendices.

Reading, for me, is an exploratory pursuit as well as a journey of self-knowledge, an affirmation of sorts. And reading leads to further reading. And reading breeds writing. It is not the cause of a story, not the impulse, just part of the process of that particular story unfolding.

- Boxiana; or, sketches of ancient and modern pugilism Pierce Egan (1830)

- Prizefighting: The Age of Regency Boximania John Ford (1971)

- The Fight William Hazlitt (1822)

- THE LIFE AND STRANGE SURPRIZING ADVENTRES OF ROBINSON CRUSOE, OF YORK, MARINER: Who lived Eight and Twenty Years, all alone all alone in an uninhabited Island on the Coast of America, near the mouth of the Great River of Oroonoque; Having been cast on Shore by Shipwreck, wherein all the Men perished but himself. WITH An Account how he was at last as strangely deliver’d by PYRATES. Written by Himself. Daniel Defoe (1719)

- Sketches by Boz Charles Dickens (1836)

- The Pickwick Papers Charles Dickens (1837)

- What Shape is a Snowflake? Ian Stewart (2001)

- Russian Fairy Tales Alexander Afanasyev (1855)

- Old Peter’s Russian Tales Arthur Ransome (1916)

- Alexander 1: Tsar of War and Peace Alan Palmer (1974)

- Moscow 1812: Napoleon’s Fatal March Adam Zamoyski (2004)

- Eugene Onegin Alexander Pushkin (1833)

- A Hero of Our Time Mikhail Lermontov (1840)

- Dead Souls Gogol (1842)

- Pushkin: A Biography TJ Binyon (2002)

- The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne Gilbert White (1789)

—Emma Richler