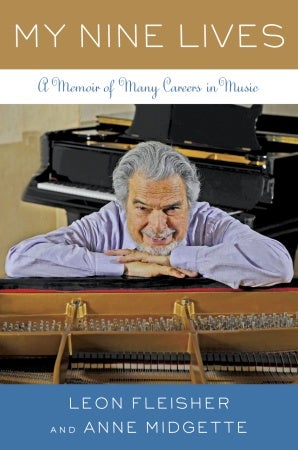

My Nine Lives: A Memoir of Many Careers in Music

The pianist Leon Fleisher—whose student–teacher lineage linked him to Beethoven by way of his instructor, Artur Schnabel—displayed an exceptional gift from his earliest years. And then, like the hero of a Greek tragedy, he was struck down in his prime: at thirty-six years old, he suddenly and mysteriously became unable to use two fingers of his right hand.

It is not just Fleisher’s thirty-year search for a cure that drives this remarkable memoir. With his coauthor, celebrated music critic Anne Midgette, the pianist explores the depression that engulfed him as his condition worsened and, perhaps most powerfully of all, the sheer love of music that rescued him from complete self-destruction.

Miraculously, at the age of sixty-six, Fleisher was diagnosed with focal dystonia, and cured by experimental Botox injections. In 2003, he returned to Carnegie Hall to give his first two-handed recital in over three decades, bringing down the house.

Sad, reflective, but ultimately triumphant, My Nine Lives combines the glamour, pathos, and courage of Fleisher’s life with real musical and intellectual substance. Fleisher embodies the resilience of the human spirit, and his memoir proves that true passion always finds a way.

BUY THE BOOK:

AMAZON | BARNES & NOBLE | BORDERS | INDIEBOUND | POWELL’S | RANDOM HOUSE

Musical Excerpts

In the course of My Nine Lives, Leon Fleisher talks a lot about the music he loves—sometimes in very specific detail. These short musical excerpts help illustrate some of his memories, and some of his observations, for those who may not be as familiar with the works in question as he is. All are taken from recordings that are readily available from most commercial outlets.

Introduction

Page 1: I put the first disk on the record player and lowered the needle, and a dark roll of timpani poured out of the big horn of the speaker, like the thunder of Thor. There followed a defiant cry from the massed forces of the orchestra, as if shaking a fist at the lowering heavens.

Brahms piano concerto no. 1 in D Minor, 1st movement; George Szell, conductor; London Philharmonic OrchestraAudio

Page 5: And I began playing, with both hands, the Brahms D Minor concerto, at the point where the long orchestral introduction ends and the piano finally makes its entrance.

Brahms piano concerto no. 1 in D Minor, 1st movement; Leon Fleisher, piano; George Szell, conductor; Cleveland OrchestraAudio

Chapter 1

Pages 22-23: The great Artur Schnabel, sitting next to me, was playing a Beethoven scherzo, giving a lilt to its lighthearted opening, moving on into more darkly shaded areas, returning to the lilt, playing light as air and with a twinkle in his eye. It was one of the most extraordinary musical experiences of my short life.

Beethoven piano sonata op. 2, no. 2, 1st movement; Artur Schnabel, pianoAudio

Chapter 2

Page 35: Once, when I was in my teens, I got to hear Schnabel rehearse the Adagio of Mozart’s piano concerto K. 467… It’s an angelic theme, and the way Schnabel played it, it was suspended in midair. It sounded like the language of the spheres.

Mozart piano concerto no. 21 in C, K. 467, 2nd movement; Artur Schnabel, piano; Malcom Sargeant, conductor; London Symphony OrchestraAudio

Master Class I – Brahms Piano Concerto No. 1 in D Minor, Op. 15

Page 59: That recap [in the second movement] is genius too. Shortly after the piano comes in, the basses and cellos hold out this long note on D —what’s known as a pedal point, meaning that the held note sustains the harmony while all kinds of other things are going on above it. In this case the piano, thundering out over that dark long note, ascends to heaven, rising up, triumphant. Then the winds come in while the piano embarks on a cascade of big arpeggiated chords. It’s very tempting to turn those chords into tidal waves, but you have to be careful not to drown out the lone flute up at the top of the chord, so there are balance challenges and questions of restraint even at a moment of abandon.

Brahms piano concerto no. 1 in D Minor, 2nd movement; Leon Fleisher, piano; George Szell, conductor; Cleveland OrchestraAudio

Page 59: Then there’s the second-movement cadenza…. The trill begins in one hand and the other hand takes over as a tritone. And then the same thing happens an octave higher. And again. The fourth time you get up there, the trill still shimmering, it’s as if you’ve reached an apex and the sun comes out.

Brahms piano concerto no. 1 in D Minor, 2nd movement; Leon Fleisher, piano; George Szell, conductor; Cleveland OrchestraAudio

Page 61: Brahms starts with one of his favorite melodic progressions, a fourth followed by a whole step followed by a whole step (or a half step, if it’s in a minor key)—or, to put it in more prosaic terms, the start of the song “How Dry I Am.” … Here, it kicks off a rousing gypsy dance.

Brahms piano concerto no. 1 in D Minor, 3rd movement; Leon Fleisher, piano; George Szell, conductor; Cleveland OrchestraAudio

Chapter 5

Pages 106-107: When we were recording the Beethoven B-flat concerto, my old standby, he couldn’t get the orchestra to play the opening tutti to his satisfaction… I went up to him on the podium and said, “I think if they played it a little more debonair.” He loved it. He immediately latched on to the word, turned to the orchestra, and said, “Gentlemen, more debonair…” If you listen to that recording, you can hear that debonair quality, right at the start: like Charlie Chaplin walking down the Champs-Élysées.

Beethoven piano concerto no. 2 in B-flat, 1st movement; Leon Fleisher, piano; George Szell, conductor; Cleveland OrchestraAudio

Page 109: Rachmaninoff is rather heavy on the schmaltz factor. I can’t quite believe my memory on this, but I could swear now that when we reached the eighteenth variation [of the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini] —the most famous section of the piece, a big, goopy crowd-pleasing tune that’s appeared on several film soundtracks—Szell mouthed to the players, “Like the Philadelphia Orchestra!”.

Rachmaninoff Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, variation XVIII; Leon Fleisher, piano; George Szell, conductor; Cleveland OrchestraAudio

Page 138: The passage that I always wait for in that piece comes in the final movement, where the piano and the oboe have a duet, tossing a tune back and forth. That’s always a heartbreaker for me. The principal oboe of the Cleveland Orchestra in those years was Marc Lifschey, an exquisite musician and an Olympian player, just phenomenal. When we started sending that tune back and forth, it was like firebolts across the heavens, except that instead of fire the substance was something immeasurably sweeter, enveloping, like cotton candy.

Mozart piano concerto no. 25 in C, K. 503, 3rd movement; Leon Fleisher, piano; George Szell, conductor; Cleveland Orchestra, Marc Lifschey, oboeAudio

Master Class II – Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Major, Op. 58

Page 141: [Beethoven’s] fifth [piano concerto], the “Emperor,” is the most majestic… Its opening is a wonderful example of the way Beethoven puts his music together. You have a huge E-flat Major chord from the whole orchestra. Except that one note is missing. Everyone is playing E-flat and G, up and down the staff, but there’s no B-flat in that chord. Then the piano comes in with this big, sweeping arpeggiated entrance up the keyboard, and when it gets to the top it goes straight for the B-flat, over and over, just in case you missed it in the opening chord. It plays that B-flat nine times. As if it were saying, Here it is! Here I am! Get it? Wow!

Beethoven piano concerto no. 5 in E-flat, “Emperor,” 1st movement; Leon Fleisher, piano; George Szell, conductor; Cleveland OrchestraAudio

Pages 141-142: The opening of the Fourth Concerto sounds almost improvised, and its oddness is emphasized when the orchestra picks it up in a slightly different key. It’s an off-kilter beginning, and not only because of the key change. In most classical pieces, phrases happen in multiples of two or four…. The opening phrase of the Fourth Concerto, however, extends over five bars. This, like the key change that follows it, gives the piece the character of a three-legged stool.

Beethoven piano concerto no. 4 in G, 1st movement; Leon Fleisher, piano; George Szell, conductor; Cleveland OrchestraAudio

Page 142: Klemperer… insisted that you maintain whatever tempo you have right at the end of the cadenza when the orchestra comes in… If you don’t give in to the impulse to get faster but hold out with the more spacious tempo, the whole thing becomes almost like a slow-motion sunrise, except that the sun is right next door.

Beethoven piano concerto no. 4 in G, 1st movement; Leon Fleisher, piano; George Szell, conductor; Cleveland OrchestraAudio

Page 142: The climax of the [second movement] cadenza, with a big crescendo building up to a trill and these little anguished cries of descending notes, could be the moment Orpheus looks back as he is leading his beloved Eurydice out of Hades and loses her forever. I think it was Emanuel Ax who told me that.

Beethoven piano concerto no. 4 in G, 2nd movement; Leon Fleisher, piano; George Szell, conductor; Cleveland OrchestraAudio

Master Class III – Ravel Piano Concerto for the Left Hand in D Major

Page 168: There’s a long trill in the middle of the Concerto for the Left Hand that… starts in the piano. Then the violins pick it up. Then all four horns come in with it, then the flute, then the clarinet. Each instrument is playing the same note, but each one, obviously, sounds quite different. Still, the whole point is that it’s one single trill: it just keeps changing the way it sounds… When it’s done right, it should sound like one long line. The whole passage is over in a few seconds. Then it leads into a delicate section that sounds like Chinese dolls taking tiny porcelain steps.

Ravel piano concerto for the left hand; Leon Fleisher, piano; Sergiu Comissiona, conductor; Baltimore Symphony OrchestraAudio

Page 169: The left-hand concerto … opens with a huge jump that’s an extraordinary gesture of unsheathing one’s sword. This comes off only if you take your life in your hands and fling your left hand up the keyboard, risking missing the jump entirely. It’s quite an embarrassment if it doesn’t come off.

Ravel piano concerto for the left hand; Leon Fleisher, piano; Sergiu Comissiona, conductor; Baltimore Symphony OrchestraAudio

Pages 169-170: The piece is born out of the murk… It starts with a rumble from the double basses and cellos, the lowest string instruments in the orchestra. There’s something very primal about the sound of open strings on the double bass. Ravel divides the basses into three sections: two of them play on open strings, and the third fills the space in between with a running flow of rapid notes, very softly, so that the chord resonates and shimmers. Then, out of this primordial slime, there rises the gravelly, gutteral, impossibly deep sound of the lowest wind instrument, a contrabassoon.

Ravel piano concerto for the left hand; Leon Fleisher, piano; Sergiu Comissiona, conductor; Baltimore Symphony OrchestraAudio

Page 171: In that cadenza… just before the first statement of the theme, there’s a little transition section of a measure or two where everything slows down, ending with three emphatic chords. For years, I really took advantage of the resonance down in the bass to make as big a sound as possible on those chords before releasing the pedal and clearing out all the resonance so that when I came in with the theme it felt like I was starting again fresh. But after a while, I’d had enough of that approach. I decided it was better to let the whole thing settle down a bit before starting the theme, so I started playing those three chords more softly.

Ravel piano concerto for the left hand; Leon Fleisher, piano; Seiji Ozawa, conductor; Boston Symphony OrchestraAudio

Master Class IV – Mozart Piano Concerto No. 25 in C Major, K. 503

Page 241: It’s quite a regal and openhearted piece. It starts with an extended and rather majestic-sounding orchestral section in C Major… The music keeps shifting and changing, like the play of light over water. Time and again, it dips into the minor mode and is then pulled up by chains of ascending sixteenth notes, brought back out into the sunlight.

Mozart piano concerto no. 25 in C, K. 503, 1st movement; Leon Fleisher, piano; George Szell, conductor; Cleveland OrchestraAudio

Page 241: The second theme of the first movement goes through lots of those major-minor shifts: now a somber meditation, now back to its spritely, vivacious self. It’s the same “How dry I am” motif that Brahms so loved, and it evokes other familiar tunes. Once, when I was rehearsing the piece with George Szell, I added a little fillip of notes at the end of the theme that turned it into the start of “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen,” one of Papageno’s songs from The Magic Flute.

Mozart piano concerto no. 25 in C, K. 503, 1st movement; Leon Fleisher, piano; George Szell, conductor; Cleveland OrchestraAudio

Page 242: There are these great leaps in that second movement of K. 503, where the piano line jumps an octave or more. Tradition, and the musicologists, will tell us that a pianist in Mozart’s time would have filled in those gaps with little improvised scales and arpeggios…But the great soaring of the spirit is lost, I think, if you fill them in. I just try to soar up there and come back down, and soar up again.

Mozart piano concerto no. 25 in C, K. 503, 2nd movement; Leon Fleisher, piano; George Szell, conductor; Cleveland OrchestraAudio

Page 243: I’m convinced that Mozart was always playing around with irreverence. So when the trumpets come blatting in with these decisive, loud chords, right at the end of the concerto, it’s like thumbing his nose. He’s just having fun with everybody.

Mozart piano concerto no. 25 in C, K. 503, 3rd movement; Leon Fleisher, piano; George Szell, conductor; Cleveland OrchestraAudio

Master Class V: Franz Schubert: Sonata in B-flat Major, D. 960

Pages 266-267: The second movement is also sublime… Time stops. You have to keep nudging it ahead, imperceptibly, to keep it moving just barely forward, while you’re lost in contemplation. I think of it as like rowing a boat: you take a stroke of the oar, and the boat moves ahead but starts to slow down, until you take the next stroke of the oar to keep it going… Once you think of it like that, you can start to play with where you think the main impulses—the strokes—need to come…

Schubert piano sonata in B-flat, D. 960, 2nd movement; Leon Fleisher, pianoAudio

Page 267: What happens next, in that recapitulation, is to me one of the most divine moments in all of music. The movement is in the key of C-sharp Minor, but Schubert takes it into the dominant, G-sharp Major for a while. Then he pauses. And then the music comes in in the key of C Major, radiant, suspended, angelic. It’s heart-stopping. It’s one of the great, great inspirations in all of the music I’ve ever played or ever heard. It certainly is a vision of heaven.

Schubert piano sonata in B-flat, D. 960, 2nd movement; Leon Fleisher, pianoAudio

Page 267: Schubert keeps punctuating the [fourth] movement with a little horn call on a G octave that sounds at the start of the main theme and every time the theme comes back. Then, suddenly, in the coda at the end of the movement, he lets that octave slip down to an F-sharp. Eyebrows have to be raised. What is that? Oh, he says innocently, that’s nothing, look: that’s just a passing tone that resolves into an F. You can hear his eyes twinkle behind his glasses. Just kidding. Then he grabs you up and races the whole thing pell-mell to a rousing close.

Schubert piano sonata in B-flat, D. 960, 4th movement; Leon Fleisher, pianoAudio

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Born in San Francisco, LEON FLEISHER made his Carnegie Hall debut at sixteen. He was Musical America's Instrumentalist of the Year in 1994; the subject of the 2006 Oscar-nominated short documentary Two Hands: The Leon Fleisher Story; and a 2007 Kennedy Center Honoree. He continues to tour the world on an ambitious performance schedule.A Yale graduate, ANNE MIDGETTE reviewed classical music for the New York Times before becoming chief classical music critic for the Washington Post.

Imprints

Featured Sections

Use of this site indicates your consent to the Terms of Use. Copyright © 1995-2024 Random House Inc. All rights reserved.