Reading Group Center

- Home •

-

Books by Category •

- Imprints •

- Authors •

- News •

- Videos •

- Media Center •

- Reading Group Center

Newsletter

Sign up for the Reading Group Center Newsletter

Reading Group Resources

Reading Group Guides

Reading Group Tips

News & Features

Connect with Us

One Book, One Community

Community-based reading initiatives are a growing trend across the country, and we're pleased to support these programs with a wide range of resources.

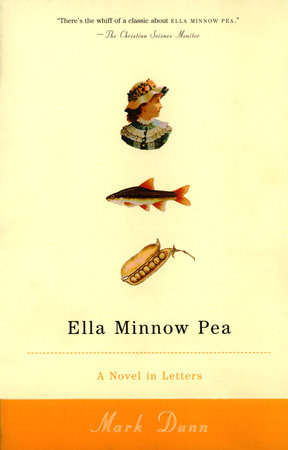

Ella Minnow Pea: A Q&A with Mark Dunn

Ella Minnow Pea by Mark Dunn is one of the most unique pieces of fiction you are likely to read. Published twenty years ago and told through a series of letters, it’s a hilarious and moving story of one girl’s fight for freedom of expression on the fictional island of Nollop. When the island’s Council decides to ban the use of certain letters of the alphabet, a ban which they progressively expand over the course of the novel (and which is reflected in the increasingly creative spelling), Ella finds herself acting to save her friends and family from the Council’s totalitarianism.

Ella Minnow Pea is a linguistic tour de force, and it is sure to delight readers of all stripes. We sat down with Mark Dunn to ask him about this incredible book, and why he thinks its appeal continues to endure to this day.

Reading Group Center: How would you describe Ella Minnow Pea in twenty-five words or less?

Mark Dunn: The novel imagines an island nation in which letters of the alphabet are incrementally outlawed, communication crippled, the very concept of freedom placed into question.

RGC: What was your inspiration for writing the book? How did you come up with the creative concept of using fewer and fewer letters as the story progresses?

Mark Dunn: To be honest, I was first driven by several companion challenges. First, to write a book whose structure would be unique. I learned from my research (at the time I was working in the New York Public Library’s Rare Books and Manuscripts Division and did lots of prowling of the stacks) that a good many writers had tackled lipogrammatic work in the past. Yet they would usually limit themselves to the loss of a single letter of the alphabet or put themselves through the paces of writing something that repeats a poem or story in different permutations, each one removing a different letter—all under the moniker of literary mischief! (I remember, as a kid, how much I enjoyed reading “Mary Had a Little Lamb” presented in twenty-six different lipogrammatic incarnations.) But I came to learn that no one had yet told a progressively lipogrammatic story (and especially not in a book-length format). I decided to push the envelope and hope it wouldn’t tear! I was also challenged by how to write a colorful story while one by one the pigments the writer is allowed to use are being taken away from him.

Finally, around the time I was considering writing this book I was struck by the degree to which religion and weaponized ideology in other parts of the world required the destruction of the work of those whose literary and artistic voices didn’t align with the voices and rigid belief systems of those in positions of power (something that hasn’t gone away). I felt that my story could make a strong statement about how a society could literally become dismantled through restrictions placed on perhaps our greatest freedom as human beings (next to the freedom to actually exist): our ability to communicate with one another.

RGC: The act of writing Ella Minnow Pea must have been quite a challenge. What was your process like?

MD: Great question because I did something I rarely do both as a novelist and a playwright. Rather than swing, trapeze-like, into my story without a net and see if my characters will catch me, with Ella I had to chart where the book would go, create a narrative trajectory that would take the reader to an important place at the end and not send them over a cliff. (My idea was never to force my characters to use fewer and fewer letters of the alphabet until all communication stopped. Not “happily ever after. The end.”) I have too many plays and novels and short stories for which I was never able to complete the arc, to finish the narrative journey, and these projects never see the light of day. Yet, for Ella Minnow Pea to succeed, the progressive outlawing of letters of the alphabet had to culminate in something to offer satisfying closure for the reader.

And so . . . drum roll please . . . I wrote the ending of the book first, knowing exactly where I wanted to end up. Then the big challenge was how to get there with such a ridiculously narrowing diminution of language to fall back on! As far as deciding the sequence of the letters destined to disappear from the story (and from the book itself) I foolishly believed I could simply remove them in inverse order of their frequency of use in the English language. And yet, if one is to believe that the letters are disappearing from the cenotaph that drives the story, not in a programmed order but haphazardly, the order that I lazily presumed simply wouldn’t work. First, I removed Z, then Q, then J, and then could no longer put off the inevitable: an important letter needed to go. I chose D. And suddenly my own linguistic adventure ramped up to eleven. (Try talking about the past, or about the days of the week without using the letter D!)

RGC: The book is made up of a series of notes between characters. How did you land on this structure? In what ways do you think it helped you tell the story more effectively?

MD: I frequently tell people who ask why I wrote this story as an epistolary novel that I couldn’t have written it any other way. (And after all these years, I still believe that.) Only through my surrendering the story to my characters can readers get a true sense as to how difficult it was for the Nollopians to communicate with use of fewer and fewer letters of the alphabet, as readers watched my characters’ struggles unfold right on the page and without a narrator’s full-alphabet intrusion. And, frankly, I could never have enjoyed writing this book if I didn’t put myself through the same linguistic difficulties as my characters. Nor do I think it would be much fun for the reader to have a detached omniscient third-person narrator, who’s given special license to break the very rules he’s forcing his characters to abide by (or to violate at their peril).

RGC: Ella Minnow Pea was first published in 2001. To what do you attribute its ongoing popularity?

MD: I don’t think you can discount its uniqueness and how it experiments with language and linguistics in a fun, even mischievous way. I know that it’s on a lot of middle and high school English reading lists, partly because of what it has to say about how sacred our ability to communicate with one another is without being arbitrarily and/or politically or theocratically censored. That words matter, that freedom to communicate should be inviolate in a free society. But I also think that there are those who appreciate that there isn’t just one way to tell a story, that experimentation with narrative can still result in something accessible and engaging for a reader. I like to say to young readers who want to be writers: There are no rules when it comes to telling your stories. Learn the rules, then feel free to break the rules. Even more satisfying: Write your own rules, challenge yourself to tell your stories with one eye closed and one hand tied behind your back, and see what you can accomplish.

RGC: What’s it like to revisit a book that you wrote so long ago? Are there any changes or edits you would make to the story if you were writing it today?

MD: We writers always think we can improve on work we’ve closed the book on, so to speak, work from the earlier epochs of our lives, and I know that nothing I write couldn’t benefit from another draft. But I’m smiling because I was just wondering aloud to my wife a couple of nights ago if I could have been just a little more creative in terms of the words I drew from our collective lexicon for the book. Not just those familiar words and phrases that might have served the story better, but also words I might choose to manipulate or brazenly misspell for story purposes, or make up myself (I think there are, even so, over one hundred neologisms in the book). What if I’d had today’s internet at my disposal, or, instead of writing Ella using only a collegiate dictionary, I’d employed an unabridged dictionary instead! (Thankfully, the word-search feature of my 2001 word processing software allowed me to word-search on those nasty illicitabeticals so that none slipped embarrassingly into my book. Otherwise, I would have been forced to tape down those typewriter keys that produce the illegal letters. Just as Mr. Ernest Vincent Wright did for his infamous “e”-less 1939 novel Gadsby. (I use the word “infamous,” because when I went looking for this quixotically celebrated novel at the New York Public Library, I was directed to a special cage that contained largely pornographic books. Gadsby isn’t pornographic, but there weren’t a lot of copies around, and its rarity directed it to a high-security location in the stacks!)

RGC: If you were to pose one question to book clubs discussing the book, what would you ask and why?

MD: Careful not to give away the ending for those who haven’t read the book . . . but there is a story flag that gets planted two-thirds of the way through the book, a signpost that tells a very observant reader where the story is headed and, indeed, hints strongly at how things get resolved for Ella and her beleaguered fellow islanders. I like to ask at book events, where I’m speaking with those who have already read the book, if they noticed that flag, or if they passed it by. Perhaps one out of five readers tells me they saw it and knew what it meant. To the others, the ending came as a big surprise (and would inevitably have them flipping back to see how they missed it). Over the last twenty years I’ve had incredible fun interacting with readers of this book. But it’s still hard to convey to readers how much fun I had writing it. People sometimes ask me, “When will you give us another Ella Minnow Pea?” How do you answer a question like that?