Reading Group Center

- Home •

- Books by Category •

- Imprints •

- News •

- Videos •

- Media Center •

- Reading Group Center

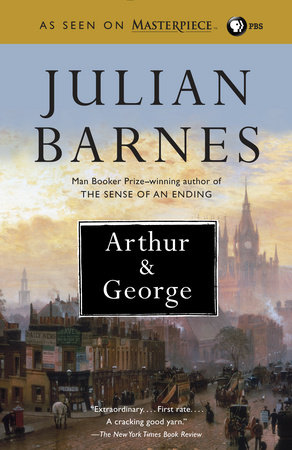

Arthur & George

By Julian Barnes

1. One of the first things we learn about George is that “for a start, he lacks imagination” [p. 4]. George is deeply attached to the facts, while Arthur discovers early in life the “essential connection between narrative and reward” [p. 14]. How does this temperamental difference determine their approaches to life? Does Barnes use Arthur and George to explore the very different attractions of truth telling and storytelling?

2. What qualities does the Mam encourage in Arthur? How does Arthur’s upbringing compare with George’s? What qualities are encouraged in George by his parents? What does the novel imply about one’s parents as a determinant in character development?

3. To what degree do George’s parents try to overlook or deny the social difficulties their mixed marriage has produced for themselves and their children? Are they admirable in their determination to ignore the racial prejudice to which they are subjected?

4. Critic Peter Kemp has commented on Julian Barnes’s interest in fiction that “openly colonises actuality—especially the lives of creative prodigies” [The Sunday Times (London), June 26, 2005]. In Arthur & George, the details we read about Arthur’s life are largely true. While the story of George Edalji is an obscure chapter of Doyle’s life, its details as presented here are also based on the historical record. What is the effect, for the reader, when an author blurs the line between fiction and biography or fiction and history?

5. From early on in a life shaped by stories, Arthur has identified with tales of knights: “If life was a chivalric quest, then he had rescued the fair Touie, he had conquered the city, and been rewarded with gold. . . . What did a knight errant do when he came home to a wife and two children in South Norwood?” [p. 69]. Is it common to find characters like Arthur in our own day? How have the ideas of masculinity changed between Edwardian times and the present?

6. George has trouble believing that he was a victim of racial prejudice [p. 264]. Why is this difficult for him to believe? Is it difficult for him to imagine that others don’t see him as he sees himself? Does George’s misfortune seem to be juxtaposed ironically with his family’s firm belief in the Christian faith?

7. The small section on pages 91–92, called “George & Arthur,” describes an unnamed man approaching a horse in a field on a cold night. What is the effect of this section, coming into the novel when it does, and named as it is?

8. Inspector Campbell tells Captain Anson that the man who did the mutilations would be someone who was “accustomed to handling animals” [p. 97]; this assumption would clearly rule out George. Yet George is pursued as the single suspect. Campbell also notes that Sergeant Upton is neither intelligent nor competent at his job [p. 99]. What motivates Campbell as he examines George’s clothing and his knife, and proceeds to have George arrested

[pp. 117–123]?

9. George’s lawyer, Mr. Meek, is amused at George’s sense of outrage when he reads the factual errors and outright lies in the newspapers’ reports of his case [p. 137; 140–141]. Why is Mr. Meek not more sympathetic?

10. George’s arrest for committing “the Great Wyrley Outrages” [p. 176] causes a stir in England just a few years following the sensational killing spree of Jack the Ripper, which sold millions of newspapers. Are the newspapers, and the public appetite for sensational stories, partly responsible for the crime against George Edalji?

11. How does Barnes convey the feeling of the historical period of which he writes? What details and stylistic effects are noticeable?

12. England was extremely proud of its legal system; Queen Victoria had expressed outrage over the injustice in the dubious case against Alfred Dreyfus, which had occurred a few years earlier in France. Yet the Edalji case seems to present an even greater injustice, and again because of the ethnicity of the accused. Why might the Home Office have refused to pay damages to Edalji?

13. For nine years, Arthur carries on a chaste love affair with Jean Leckie. Yet he feels miserable after the death of his wife, Touie, particularly when he learns from his daughter Mary that Touie assumed Arthur would remarry [pp. 247–49]. Why is Arthur thrown into “the great Grimpen Mire” by his freedom to marry Jean [p. 253]? Why does he believe that “if Touie knew, then he was destroyed” [p. 305]? Has he, as he fears, behaved dishonorably to both women? What does the dilemma do to his sense of personal honor?

14. Why is the real perpetrator of the animal killings never identified? In a Sherlock Holmes story the criminal is always caught and convicted, but Doyle gets no such satisfaction with this real-world case. How disturbing is the fact that George is never truly vindicated and never compensated for the injustice he suffered? Does Barnes’s fictional enlargement of George Edalji’s life act as a kind of compensation?

15. Arthur & George presents a world that seems less evolved than our own in its assumptions about race and human nature, justice and evidence, and its examples of human innocence and idealism. Does this world seem so remote in time as to be, in a sense, unbelievable? Or might American readers recognize a similar situation in a story like Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, or more recent news stories about racial injustice?

16. The story ends with George’s attendance at the memorial service for Arthur. What is most moving about this episode?