- Home •

- Books by Category •

- Imprints •

- News •

- Videos •

- Media Center •

- Reading Group Center

Judith & Julia's Steps Through Paris: Mastering the Art of French Coping

About two weeks ago, this very fortunate Borzoi Cook got on a plane and took a trip from the Big Apple to the City of Lights: Paris, the city Americans have looked to for years for a guide to cuisine, style, and to living a life full of pleasure and sophistication. During my week-long stay, I was especially keen to visit the sights most immediately associated with two Knopf icons that spent extended periods of time in Paris: Julia Child, and Judith Jones.

Having read both of Julia and Judith’s stories (for Julia, My Life in France; for Judith, The Tenth Muse) of their early years in Paris, and having immersed myself in fantastical visions of the city by way of Gene Kelly, Billy Wilder, and Audrey Tautou, I was full of the belief that, if I really made an attempt at doing Paris right, I could include myself among the successful “Js” that made the voyage.

Julia first came to Paris in her late forties, barely certain of anything except that she loved traveling with her husband, Paul, a well-versed Francophile and someone equipped to show her around their new city. Her first extraordinary meal, that infamous sole meunière which she said carried the “light but distinct taste of the ocean that blended marvelously with the browned butter,” was not actually experienced in Paris—rather, it was at a tiny restaurant in Rouen (near Normandy) called La Couronne (The Crown). This was obviously not the only spectacular meal Julia would have in France, but for me this spectre of culinary bliss hung high, like Proust’s infamous Madeleine and James’s giant peach. (Literature incites people to desire many things, but I’ve always been a sucker for great descriptions of fantastic food.) Julia’s sole, in particular, was inspiring to me because it filled her with a kind of buoyancy that is hard to come by when traveling in a somewhat unknown land. With that first flaky bite of perfect fish, she was empowered to seize onto France for all its potential, culinary and otherwise. She recounts her post-sole attitude as one with a broad smile and bad pronunciation. “‘Mairci, monsoor,’ I said, with a flash of courage and an accent that sounded bad even to my own ear. . . . Paul and I floated out the door into the brilliant sunshine and cool air. Our first lunch together in France had been absolute perfection. It was the most exciting meal of my life.”

Judith’s path to Paris, meanwhile, had been a little different. She came as many young people have come to foreign countries, as a student of French culture. Together with a friend from college, she was photographed for the cover of Life magazine, a young American girl building sandcastles on the coast off Normandy for a feature on all the young people flocking to Europe in the summer of 1948. Judith waxed rhapsodic about this period with me in the Knopf offices just after I’d returned from Paris. “We were arriving just after the war, and so the French just loved us. Of course, in just a few years we would see signs saying ‘Yankee Go Home’, but for now it was lovely.”

Judith tried to take in everything, culinarily-speaking: from cafés and brasseries that served up sole meunière and cervelle de (brains in butter and capers) to the perfect picnic lunch of baguette and pate in a nearby square. When she turned her brief French expedition into a longer stay, she converted her shared apartment into a tiny restaurant: “Maybe we could pay for feeding ourselves by feeding others?” Her living room became a dining room, and all those hungry guests forced her to learn how to select ingredients and cook something spectacular at a moment’s notice, to treat cooking as an art and a calling.

For a period, it was hard to be an American in Paris and not find yourself in good company—from the late 1940s-early 1950s, the city was flooded with not only tourists, but artists, intellectuals, people hungering for a taste of whatever Paris could offer. Judith and Julia both took the city into their homes—Judith, by becoming a gourmet as a trial-by-fire; Julia, by opening up her apartment at 81 rue de l’Universite (Roo de Loo, she called it) as the site of classes taught by herself and her friends and future co-authors, Simone “Simca” Beck and Louisette Bertholle. Roo de Loo is hard to miss, running through the Sixth and Seventh Arrondisement (from Saint-Germain to the Esplanade des Invalides), but I found it by accident, during my first day of long, directionless walking in the city.

My first day in Paris, I got deeply, irrevocably lost, and in trying to head toward Notre-Dame and instead heading toward the Louvre, I took a wrong turn on Rue de Saints-Péres and soon found myself facing the sign for Rue de Loo. I can only imagine the relief the newly transplanted Julia must have felt at this same realization 60 years beforehand . . .

It’s an unassuming street, pale brick buildings with little window shutters thrown apart to reveal flowers, laundry, occasionally a small cat or child whose red balloon had decided to take a stroll. But looking up at one of the apartments at Julia’s address, with its open shutters, I could almost picture her standing beside it, letting the breeze waft through her overheated kitchen, watching the passersby and letting out a hearty “Bonjour” to the salespeople she knew from her local haunts.

Day 2: Walking by Julia’s apartment inevitably got me to thinking about food—and searching for food the way a true French cook might, in the open air markets at Les Halles.

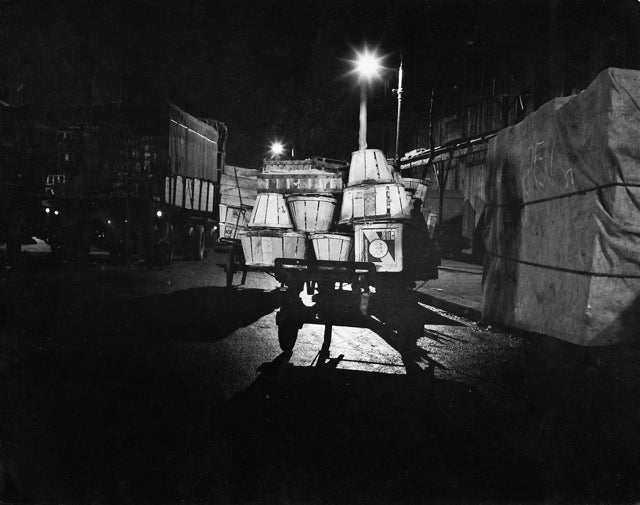

Les Halles, in Julia’s time

In Julia’s heyday, the wholesale market featuring the farmers, butchers, bakers, and fishmongers of Paris would gather in the first arrondissement to sell their goods, leading to the area’s nickname by Emile Zola, “Le Ventre de Paris (the Belly of Paris).” Zola was primarily speaking of the area as a belly because of its hollows and valleys, like the empty basin of the city, but he may as well have been speaking of its culinary satiation: everyone that wanted to eat came to Les Halles. In the 1970s, the open markets were shuttered to make way for what is now the Forum des Halles, a massive underground shopping center. But in the narrow streets surrounding the former marketplace, the farmers still show up, and so do the customers.

In both of their memoirs, Julia and Judith couldn’t help but gush over French ingredients. Judith wrote home about the open-air markets “bursting with fresh produce . . . Sometimes it was hard to resist when the first spring morels, or tiny fraises des bois were decoratively displayed—delicacies that seemed so out of this world to me that I was always afraid they would be all snatched up before I could make the return trip.” She learned by walking through these markets, how after purchasing a daurade, “I asked the fishmonger how to cook it and, with customers waiting, he explained exactly how it should be done. . . . Those impecunious days were full of inventiveness and fresh discoveries.”

I was tempted to use my one linguistic weapon—the vocabulary of food—to prod the fishmongers and butchers for their recommendations, but it was easier to follow Julia’s inspirations: the fresh fruits and vegetables that lent to nibbling while on long walks through the city. Julia wrote extensively about the surprises of French food: “the great big juicy pears grown right there in Paris, so succulent you could eat them with a spoon. And the grapes! In America, grapes bored me, but the Parisian grapes were exquisite, with a delicate, fugitive, ambrosial, and irresistible flavor.”

post-Paris, what I’ve noticed most is how much attention Julia paid to heightening the contribution of each ingredient to the finished dish. Too much notice has been given to her use of butter, and not nearly enough to her appreciation of how to make the most of every flavor available. In making Mastering the Art of French Cookingboeuf bourguignon

I could have smuggled six of these home with me . . . for shame.

Strolling through these fresh markets inevitably got me thinking about cooking—fortunately, I was near the very place Judith had urged me to visit while in Paris: the famous kitchen supply store, and a regular haunt of both Julia and Judith’s, E. Dehillerin Matérial de Cuisine.

Both Julia and Judith rave about this store in their own way—a famously high-end kitchen and restaurant supply store off the Rue de Louvre, not far from the Centre-Pompidou and the original location of Les Halles. Its wide windows and cheery green clapboard exterior belies the quality of the goods inside: each item, from the smooth wood rolling pins to sleek knives and spoons nestled in wooden cubbies, copper pots and pans glinting in the afternoon light.

Though the hardware does include a few more contemporary items, there is clearly an emphasis on the traditional instruments of the well-seasoned chef—and, I was told, that is to mean professional chefs. When I asked the manager, in my best pidgin French, for the French words for mortar and pestle (one of Julia’s indispensable tools, designed for crushing herbs and seeds into pastes and powders), he sniffed a little and said, “If you don’t know the words, you needn’t speak in French.”

I was thrown. Not speak in French, even if you knew 90% of the necessary words? Wasn’t that the equivalent of coming to New York and taking all the time you wanted on a sidewalk? His attitude troubled me, not because it was rude or dismissive, but because it seemed so—well, French. While pacing away from the manager, smacking a perfectly sanded rolling pin against my palm, I started to think of all the moments where Julia seemed to be fed up with France: the arrogance of the Cordon Bleu, both the teacher who thought she’d be satisfied as an amateur, and the smirks of her male classmates as she learned to chop an onion for the first time. I recalled a note in Judith’s memoir about how Julia, as she was working with Simca on Volume 2 of Mastering the Art (best known for its 20+page recipe on authentic baguettes), was getting frustrated with Simca’s insistence on the proper French way to do things

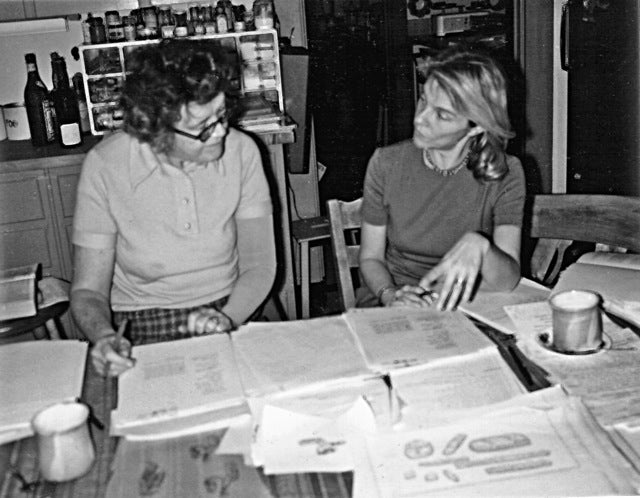

“I was in Julia’s Cambridge kitchen once when Volume II was just about completed, and a fat letter from Simca arrived. Julia started reading it aloud, doing a hilarious imitation of the French hauteur (non, non, non, ce n’est pas français), and finally she threw the letter on the floor any more and stamped on it. ‘I will not be treated like dog Tray any more,’ she cried. Paul cheered.”

I was just starting to get into a real loathing-the-French groove, and contemplated marching out of the store and toward the next tourist-ready, all-English attraction I could find. (I was fairly close to the Louvre, it couldn’t be that hard.) But then I recalled a conversation Julia and Paul had had about the necessary existence of the “Rude Frenchman”:

“Paul declared that, in Paris of the 1920s, 80 percent of the people were difficult and 20 percent were charming; now the reverse was true, he said—80 percent of Parisians were charming and only 20 percent were rude. This, he figured, was probably an aftereffect of the war. But it might also have been due to his new outlook on life. ‘I am less sour than I used to be,’ he admitted. ‘It’s because of you, Julie.’”

Paul was made less resentful of the French attitude in part because he had such an effusive traveling companion. And walking through de Hillerin, I tried to imagine Julia beside me: rather than bristling at the manager’s attitude, she saw potential in every piece of equipment (even after her triumphs on The French Chef, she still marveled at and applauded the new technology of microwaves, canning, and food processors.) You don’t have to watch Meryl Streep’s extraordinary performance in Julie & Julia to know what a force of nature like Julia would have been in a foreign city. Julia might have learned a bit of French and a lot of French cooking, but she also would’ve gotten the French to see things her way. Paul noted in a letter to his brother Charlie, “Julia makes the French love her, and so she thinks the French are wonderful.” If anyone could have found a way to charm the French, it must have been Julia.

Clutching a little skillet (perfect for a omelette, and exactly what Judith described in her latest blog post on her kitchen supplies), I handed the woman at the counter my purchase. I asked her, rather nervously, “The manager said this store was for professional chefs. That can’t be completely true, can it?”

“Oh no,” she replied, in French I could understand far better than I could speak. “Whether they are professional or just want to be, they can come here. People who work in restaurants, people who work at home—I’ll take anyone who loves to cook. Cooking is cooking, after all, there’s no rule on who is allowed to make something taste good.”

To make something taste good . . . even in the midst of a foreign country, even when heard in a foreign language, there’s something deeply empowering about cooking. It’s the essential quality that drove Julie Powell, despite her frustration at her dead-end job, to come home every night and attack a recipe with the gusto of a mad scientist, the comfort of knowing that, with a good recipe, if you add eggs and butter and chocolate and mix them together, they will get thick and taste delicious. A formula that unmovable—good ingredients, combined with the right method, will produce something sublime—is the great comfort to anyone person who endeavors to pick up a knife and do the work in the kitchen. The work of a gourmet, be it someone who cooks or someone who appreciates great cooking, is comparable to the spirit of those two women who took on Paris before me. In a letter to her parents, the neophyte Parisian Judith Bailey argued that her staying in France was not supposed to be easy, but that it was undoubtedly worth the effort: “Being in Paris is something I believe in and I hope you are convinced that it is a really good thing. . . . I shall be a well-educated girl really knowing for once something that goes on in the world.” The world, it seemed, lay in taking those moments where a store owner might snub you, and buying a pan to spite him just a little, and to make something extraordinary of which he would not get a single bit.

I smiled at the clerk, picked up my pan wrapped in brown paper, and felt not snubbed, not dismissive, but just a little discerning—a quality claimed by New Yorkers just as much as by the French. I went to Paris expecting to be less of an American, but it turns out, this new city demanded just as much nerve, and both Julia and Judith knew that for sure. Even as I had experienced the panic of getting lost on the way back that evening, I, like Julia and Judith, “wandered the city, got lost, found myself again. . . . I got along ‘assez bien.’”

And P.S. – As it turned out, I missed the sole meunière this time around. But there’s always time for another visit . . .